The Carlton Community History Group (CCHG) was established by a committed group of people interested in the history of Carlton, North Carlton and Princes Hill, three inner-city suburbs of Melbourne, Australia. CCHG was incorporated in 2007 and launched at the Carlton Library in 2008.

We invite you to explore this website, find out more about us, read our quarterly publication Carlton Chronicles, like us on Facebook, share your recollections join as a member and participate in our zoom meetings and activities.

The latest edition of Carlton Chronicles is now available.

Stories of Service and Sacrifice

Carlton During World War 2

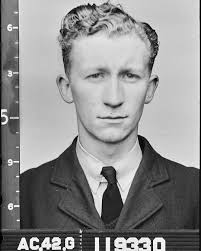

Image: NAA: A9301, 119330

Joseph Anthony Battanta of Princes Hill

Patrick Ferry from National Archives of Australia gave an outstanding presentation at the Kathleen Syme Library & Community Centre, 251 Faraday Street, Carlton, on 24 May 2025. Patrick is the Project Manager for the Digitising Services Team (Defence Services Records) of the National Archives. The topic was stories of service and sacrifice by volunteers from the Carlton area during World War Two. The case studies brought history to life as well as illustrating the methodology of the National Archives. Military historians were among those who attended. This presentation was part of an ongoing Carlton Community History Group collaboration with the Kathleen Syme Library & Community Centre. The venue offers meeting rooms available for booking and a café nearby.

The public can access digitised service records online at www.naa.gov.au or by ordering original records held in Melbourne for viewing at the Victorian Archives Centre, 99 Shiel Street, North Melbourne. The reading room is co-located with the Public Record Office of Victoria and open from Wednesday to Friday from 10.00 am to 4.30 pm.

Carlton 100 Years Ago

Fishy Business at Hardy & Co.

Image: CCHG

Commemorative Drinking Fountain at Hardy Reserve

Robert John Hardy was a well known grocery merchant and local councillor. He operated the business Hardy & Co. from premises at 216 Macpherson Street, Princes Hill, and lived at "Wahroonga", a short walk away at 870 Lygon Street, North Carlton. Hardy dealt in a range of commodities – including his signature brand of Hardy's Jelly Crystals – and food items. In 1925 he accepted a telephone order for cases of salmon, placed by a travelling salesman named Gleed, reportedly acting on behalf Harold Gordon Laidlaw. The order was duly supplied, but the invoice was never paid.

Following a police investigation the extent of Gleed's fraudulent activities was revealed. Five years previously, in April 1920, Clyde (also known as Clive) Gleed was arrested for embezzling money from the Australian Cereal Food Company in Cardigan Street. He escaped a custodial sentence in this case, but was imprisoned in June 1923 on a charge of obtaining money by false pretences. After his release from prison in March 1924, he stayed on the right side of the law for about a year, until he fleeced Harold Gordon Laidlaw and Robert John Hardy in 1925. In November 1928 he was charged with having obtained, by false pretences, 34 pairs of stockings and 5 pairs of men's hose from the Gross Hosiery Mills in Swanston Street, Carlton. Clyde Gleed – who may have been more appropriately named "Greed" – continued to commit offences and spent time in and out of prison for the next ten years. He was finally released on parole in September 1938.

ORDERS FOR FISH.

ALLEGED FALSE PRETENCES.Clive Gleed, 27 years, traveller, appeared at Carlton court yesterday on a charge of having by false pretences obtained a quantity of fish valued at £33 11/9 with intent to defraud. Robert John Hardy, merchant, McPherson-street, North Carlton, said on 7th January he received a telephone message which purported to come from Harold Gordon Laidlaw, Bank-street, South Melbourne, asking for quotations for medium red salmon, herrings and other fish. Quotations were given, and the voice at the other end of the telephone said he would take ten or twelve cases of salmon, to the value of £26 10/. A carrier called, and the fish was handed over to him. An account was sent to Laidlaw, but witness had not been paid.

Patrick Cooney, carrier, Amess-street, North Carlton, said he was told by accused to go to Hardy's for ten or twelve cases of salmon, and to say that he came from Laidlaw's, of the market. Witness obtained the fish, and took it to a shop in Separation-street, Richmond, where he saw Gleed, who sold [a] portion to the shopkeeper. The remainder of the fish was taken to a Chinese place in Exhibition-street. On the following day the fish was taken to a grocer's shop in South Melbourne by witness. Harold Gordon Laidlaw, grocer, Roy and Palmerston streets, South Melbourne, said he had done business with the accused about twelve months ago. Accused had no authority to order goods from Hardy on witness's behalf.

Detective J. W. Madin said that on 4th June he arrested accused on other charges. Witness questioned him as to ordering the goods from Hardy, and he admitted that he had no authority from Laidlaw to do so. Gleed said he had sold the fish for cash to small grocers in Melbourne suburbs. Gleed was committed for trial at the General Sessions today. Bail was allowed in £100, accused being already out on bail to the extent of £200 in connection with other charges of a similar nature.

The Age, 1 July 1925, p. 16

Robert John Hardy was first elected to Victoria Ward on the Melbourne City Council in May 1915 and represented his constituents until his death at "Wahroonga" in May 1937. He was buried at the new Melbourne General Cemetery at Fawkner, where he was on the board of management. Two years later, in August 1939, his son Frederick George Jack (Fred) Hardy was elected to Victoria Ward. Fred Hardy served in this capacity until his death in May 1975. Both father and son are commemorated by a drinking fountain at Hardy Reserve, on the corner of Lygon and Macpherson streets, directly opposite "Wahroonga".

Seventy Years of Weaving and Spinning

The Handweavers and Spinners Guild of Victoria celebrated its 70th anniversary in 2024 and has a long association with Carlton and North Carlton. The Guild was originally established as the Victorian branch of the New South Wales Guild in 1952. As interest and membership grew, the Guild became a not-for-profit organisation in its own right. The first meeting was held at the Public Library (now State Library of Victoria) in April 1954. For the next nine years, the Guild met at several city locations and in 1963 moved to the Loyal Orange Lodge at 524 Elizabeth Street, Carlton. There was another move in 1971 to the Horticultural Hall (popularly known as "Horti Hall") in Victoria Street, opposite Trades Hall. In the 1980s, the Guild became part of the wider craft movement at the Meat Market Craft Centre (MMCC) in North Melbourne. This was not to last, as the MMCC closed suddenly in 1999.1

In 2000, the Guild had to find new premises and the site chosen was in North Carlton. The scout hall at 12 to 18 Shakespeare Street dates back to the 1930s. The foundation stone was laid by the Lord Mayor Councillor Luxton in July 1930. The hall was purpose-built for public performances, with a raised platform, off-stage dressing rooms and cloakrooms. It served a dual purpose in providing a home base for the First Carlton Troop and also a source of income from hiring out the premises for public and private functions. When the Guild moved in, the building was a bit run down and had problems with water damage, but it provided a large open space for classes and workshops and a single storey setting. No need to carry bulky weaving looms and spinning wheels up and down the stairs.2

By 2011, the building was long overdue for renovation, and also required for scouting activities. Once again, the Guild had to find another home. This was a two-storey building at 655 to 657 Nicholson Street, North Carlton, a 1970s structure with a retail shopfront on the ground floor and a gym above. While not a heritage building, the new location offered more exposure in a local business and shopping precinct, with ready access to public transport. The Guild is expanding its floor space in 2025 by leasing the ground floor of the adjacent building at 653 Nicholson Street. This will provide improved access and facilities for classes and workshops. The two storey shop and its neighbour at 651 were built for Louisa Jones in 1888. The first occupants were the Harmsworth Brothers, painters & decorators, followed by a succession of businesses – confectioner, greengrocer, jeweller, cycle depot, optician, pawnbroker, chemist, real estate agent and restaurants offering a variety of cuisines. The most recent businesses have been the Koca Lane salon and Moosa Bar.3

Adding up the years, the Handweavers and Spinners Guild of Victoria has spent nearly half of its lifetime in Carlton and North Carlton, and has woven its way into our history.

1 Paramanathan, Elizabeth. Arachne's Children, 2006

2 The Argus, 21 July 1930, p. 7

3 Building ownership and occupancy information sourced from land title records, the Victorian Heritage Database, Sands & McDougall directories and newspaper advertisements.

More on Shakespeare Street

Last Tram Out of the Depot

Photo: CCHG

W7 class tram no. 1031 in prepartion for its final run out of the former tram depot in Nicholson Street.

The cranes on the right hand side were used to lift the tram onto the back of an over size load truck.

Friday 23 August 2024 marked the end of an era for W class trams in Nicholson Street, North Carlton and North Fitzroy. W7 class tram no. 1031 was the last of six W and SW class trams to be removed from the former North Fitzroy tram depot, where they had been in storage since 2014. The depot, now home to the bus company Kinetic, serviced the Nicholson Street tram route from 1956, when electric-powered trams replaced buses on the Bourke Street to East Brunswick run. 1956 was also the first year that tram no. 1031 came into service. However, the history of trams in Nicholson Street goes back as far as 1887.1

The Nicholson Street cable tram service opened in 1887 and was the first to operate in Carlton. The introduction of affordable public transport was a boon to residents and businesses on both sides of Nicholson Street, and facilitated development of the shopping precinct as far as Park Street, North Carlton. The cable trams served their purpose for decades, but they were considered an inefficient mode of transport into the 20th century. The Nicholson Street cable trams were replaced by buses in October 1940. London-style double deck buses operated for a time, but they proved inefficient at peak hour and were phased out. The service was restored with electric-powered trams in April 1956 and, with major upgrades in infrastructure and rolling stock, continues to this very day. The tram tracks leading into the depot are still visible, but a short section connecting to the main line in Nicholson Street was removed in January 2020, when the tram tracks were dug up and re-instated during installation of new accessible tram stops.2

View video clip of W7 class tram 1031 leaving the North Fitzroy depot on Friday 23 August 2024.

Notes and References:

1 https://vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams§ion=heritage&museum=north%20fitzroy

2 Jones, Russell. No stairway to heaven : the failure of double deck buses in Melbourne. Melbourne Tram Museum, 2017

"The Doll" in Carlton

Ray Lawler, acclaimed playwright, actor, director and producer, died on 24 July 2024, aged 103 years. Lawler's best known work was his stage play "Summer of the Seventeenth Doll", first performed by the Union Theatre Repertory Company at the Union Theatre, Melbourne University, on 28 November 1955. The play was set in a boarding house in Carlton in 1953, where itinerant cane-cutters Roo and Barney travelled south from Queensland each year during the summer lay off season and renewed their relationships with barmaids Olive and Pearl. The "doll" of the title refers to a decorated kewpie doll on a stick, a popular carnival novelty in the 1950s. The play was remarkable in realistically portraying the lives of working class Australians. Ray Lawler, an actor in his own right, performed in the role of Barney in the original production, directed by John Sumner. According to fellow playwright Gordon Kirby, a long term Carlton resident, Ray Lawler lived in Carlton for six months only, but the inner city suburb must have made a lasting impression on him.1,2

"Summer of the Seventeenth Doll" went on to be performed, to critical acclaim, in England in 1957, followed by a season in the United States in 1958. American audiences did not quite "get" the nuances of Australian language and culture. However, in 1959 "The Doll" was given the full Hollywood treatment with a film adaptation, directed by Leslie Norman. The screenplay was written by John Dighton and the cast featured American and British actors Ernest Borgnine, John Mills, Anne Baxter and Angela Lansbury in the leading roles. Mills took the part of Barney, originally performed on stage by Ray Lawler, and several Australian actors had supporting roles. The film was shot in Australia, but the location was moved to Sydney, with views of the harbour bridge to remind filmgoers where the action was taking place. The ending was also changed, to give it a more positive spin. The film received mixed reviews in Australia, with one reviewer summing up: "In a word … DISAPPOINTS."3

Ray Lawler lived and worked overseas for the next decade, returning to Australia in the 1970s. He wrote two prequel plays to "The Doll" – "Kid Stakes" set in 1937 and "Other Times" in 1945 – thus completing "The Doll" trilogy. The new plays were first performed by the Melbourne Theatre Company in December of 1975 and 1976 respectively. In 1978, "The Doll" trilogy returned to its original roots, with all three plays performed and filmed at the Open Stage in Carlton. This was not a feature film or television adaptation, but an authentic portrayal of the stage plays, as performed by the Melbourne Theatre Company. The plays, comprising seven and a half hours' performance time, were screened on the Channel Seven television network.4

Nearly seventy years after its premiere performance in 1955, the play has been staged extensively in Australia and overseas. "The Doll" has stood the test of time and remains a fitting tribute to Ray Lawler's body of work.

Notes and references:

1 Lawler, Ray. The Doll Trilogy : Kid Stakes, Other Times, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll. Currency Press, revised edition, 2015

2 The Australian Women's Weekly, 22 October 1958, p. 12

3 The Australian Women's Weekly, 16 December 1959, p. 66

4 The Australian Women's Weekly, 22 February 1978, p. 31

The Taggart Brothers of Nicholson Street

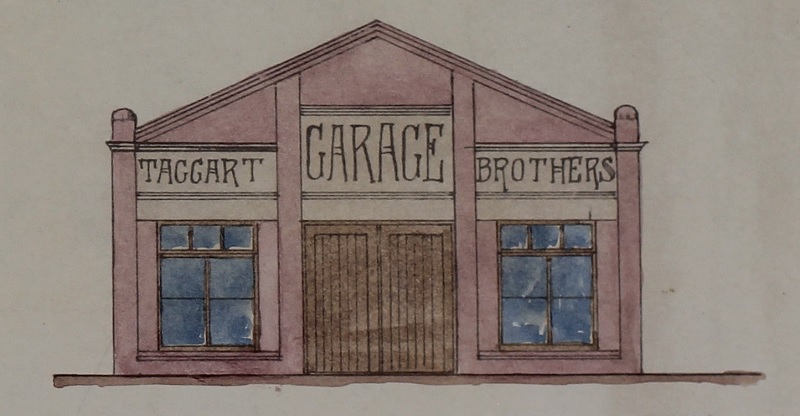

Image: Building Application Plan VPRS 11201/P1/1568

Architectural Drawing of Taggart Brothers' Garage in 1918

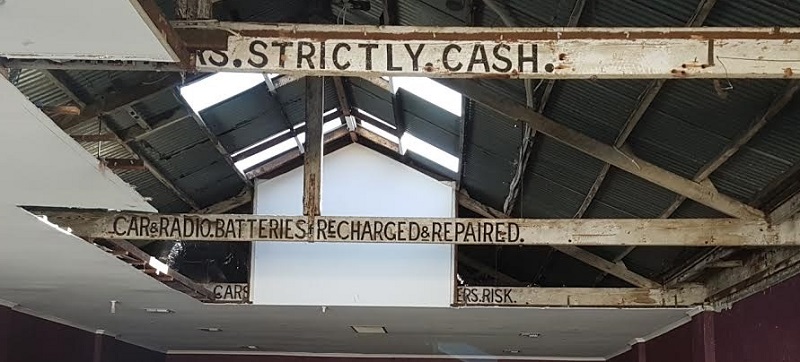

The Taggart Brothers – Alfred James and Thomas Norman, sons of Edward and Annie Taggart – were born in Fitzroy and made their living on the North Carlton side of Nicholson Street. As young men aged in their twenties, the brothers took over Fontaine's existing cycle business in a two-storey shop and residence at 699 Nicholson Street. The building was one of three terraces, originally built by Silvio De Bonis in 1889/90. Taggart Brothers began advertising as Ensign Cycle Works in 1907. Ensign was a popular brand and the brothers offered hire, repair and sales, with cycles built to order from £8 8s. A good description of an Ensign cycle was published in the Victoria Police Gazette in November 1908, when a Mr King helped himself to one.1,2,3,4

Victoria Police Gazette, 26 November 1908, p. 458

The cycle business continued at 699 Nicholson Street for the next decade, but the Taggart Brothers recognised the transition to motor vehicles as a viable business development. They expanded into the adjacent property at 695 and 697 Nicholson Street. This double block originally housed a timber boat factory, dating back to the 1880s. It served a variety of business purposes, including a plumber, furrier, estate agent, and furniture dealer. The timber building, described as a nine room house in rate books at the time, was damaged by fire in May 1898 and partly rebuilt in brick. Twenty years later, plans for a new purpose-built garage were lodged with the council in September 1918 and the works were completed by R.G. Baptie three months later in December. The wide front door, with windows either side, enabled ample access for motor vehicles. Skylights in the roof provided additional natural light in the work area.5,6,7

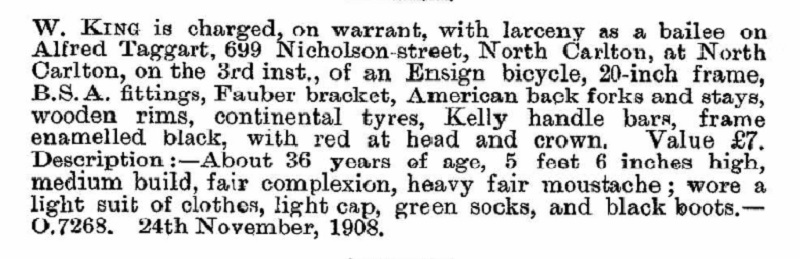

Alfred Taggart died in March 1927, just short of his 46th birthday, and the garage business was continued by his younger brother Thomas. In the mid-1930s, Thomas moved south to premises shared with Thompson & Son Motor Tyre Company at 677 to 679 Nicholson Street. Thomas Taggart died in November 1956, aged 72 years. The Taggart Brothers, together in life and business, were buried with other family members in Melbourne General Cemetery. The former garage building was bought by Henry Smith, an ironmonger, and he established his own business there, with a hardware store as a later development. In more recent times, the building was home to the video store "Video Zone", and the beauty clinic "Duquessa". Renovations for the medical clinic "Doctors on Nicholson" in 2019 uncovered signage dating back to the days of Taggart Brothers' motor garage.8,9,10

Image: CCHG

Garage signage uncovered during renovations in 2019

Notes and references:

1 Birth registration nos. 9374/1881 and 9267/1884

2 Australian Architectural Index

3 Fitzroy City Press, 8 March 1907, p. 2

4 Victoria Police Gazette, 26 November 1908, p. 458

5 Building ownership, occupancy and descriptions been sourced from land titles, Sands & McDougall directories,

Melbourne City Council rate books and building application files.

6 The Age, 16 May 1898, p. 3

7 Building Application Plan (VPRS 11201/P1/1568)

8 The Argus, 29 March 1927, p. 1

9 Thomas N. Taggart probate file (VPRS 28/P0004, 508/202)

10 Certificate of Title, vol. 4200, fol. 979

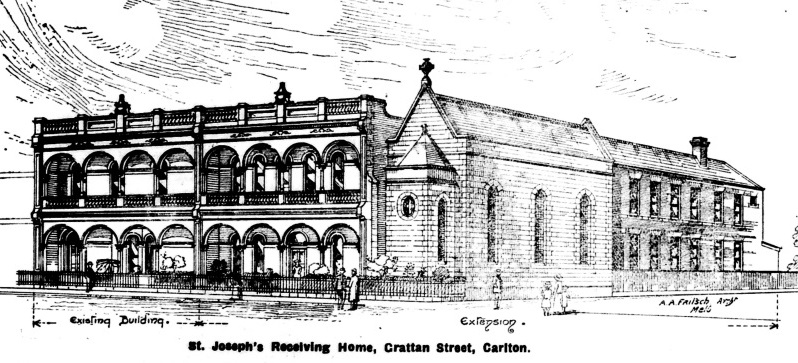

The Chemists of Hopetoun House

Image: CCHG

Hopetoun House and Gilmerton House

781 and 783 Nicholson Street North Carlton

Hopetoun House and its neighbour Gilmerton House were built by Joseph Telfer in 1892, in the last block of Nicholson Street between Pigdon and Park streets. Hopetoun House has a long history as a chemist shop, from the 1890s through to the 1970s. The first chemist to take up residence at Hopetoun was Walter Powell, who came from Bristol in England. At the young age of 16 years, Walter was listed as "chemist" in the 1871 England Census. According to the Pharmaceutical Register, he had passed the "minor exam" in Britain and was registered in Victoria in March 1887, though later advertisements state his business was established in 1885 or 1886 (possibly selling over-the-counter remedies). Walter was living in Brunswick at the time of his registration and in 1889 he bought the shop and residence at 779 Nicholson Street, next door to Hopetoun House. He and his family moved to the larger premises at Hopetoun House – with two extra rooms – in 1892. Walter Powell was to remain living and working there until his death in October 1927, while the adjacent property he owned was rented out.1,2,3

As a chemist, Walter Powell was a well known member of the community. In January 1895 he gave evidence at a coronial inquest into the death of news vendor Wesley Stockdale, who died of a brain haemorrhage. Two months later, he wrote a letter to the editor of The Argus, advising readers how to detect spurious coins (which were in circulation in Carlton at the time) with the application of "lunar caustic". This substance, known chemically as silver nitrate, was available from chemist shops and his advice most likely boosted sales of the product. From late 1899 to early 1901, Walter Powell's testimonial was used to advertise a somewhat spurious therapeutic product – Zoophyte – which claimed to cure colds, influenza and hydatids, a serious parasitic tapeworm disease. After two years of active promotion Zoophyte disappeared, without a trace, from the advertising pages.4,5

A PURE HERBAL TONIC.

An Invigorating Beverage with Extraordinary Medicinal Efficacy in cases of COLDS, INFLUENZA or HYDATIDS.Mr Walter Powell, of Carlton, as above, Victoria (Queen's Prizeman for Chemistry), writes:–

"Having analysed your ZOOPHYTE HERBAL TONIC, I can confidently recommend it as a Pure Herbal Decoction of Native Bitter Herbs. Its tonic qualities are great, more especially after an attack of influenza."Rutherglen Sun and Chiltern Valley Advertiser, 25 May 1900, Supplement, p. S2

In February 1901, Walter Powell was the victim of a young swindler named Edward Harding, a fellow Bristolian he met while travelling to Sydney on the steamship Burrumbeet. On his return home, Powell received a telegram from Harding asking for money. Like the online scammers of today, Harding claimed that he was "stranded" and needed money to pay for his passage back home. Walter Powell booked a passage to London and gave Harding some cash, on the understanding that the amount would be reimbursed by Harding's "father", of the Bristol firm Colthurst & Harding, with whom Powell had previously transacted business. He wrote to Colthurst & Harding in good faith, only to find that there was no family or business connection between the young Edward Harding and Mr Harding of Bristol. Subsequent enquiries revealed that Edward Harding had left the ship in Adelaide and cashed in the balance of his passage. He had no intention of returning to England and Walter Powell had been well and truly scammed. Following an investigation, Edward Harding was arrested in Sydney in July 1902 and escorted to Melbourne, where he faced a charge of obtaining £30 by false pretences He was sentenced to one month's imprisonment and it was unlikely that Walter Powell ever got his money back.6

The following year, in April 1902, Walter Powell and his wife Phyllis were victims of a home invasion in the early hours of the morning. A young man entered the premises via a rear window, and went upstairs into the bedroom. Phyllis called out to her husband and he chased the intruder down the stairs, but he managed to escape. All that was taken was a box of cough drops from the bedside table. A few days later, once again in the early hours of the morning, Constable Clark apprehended a young man who was acting suspiciously near the corner of Station and Macpherson streets. He matched the description of the man who had entered the Powell premises and, despite the early hour, Constable Clark took him there to be identified by Walter and Phyllis. Samuel Jamieson was charged with "burglariously entering the residence of Walter Powell", but he was found not guilty on the ground that he had an alibi at the time of the alleged offence. A young woman, claiming to be his "wife", said he had been at home with her all night. After this unpleasant experience, Walter was very much aware of the role played by police in protecting people and property. In 1904, when the local police constable was removed from evening patrols, Walter Powell penned a letter to the editor of The Argus, noting the increase in youth crime and anti-social behaviour.7,8,9

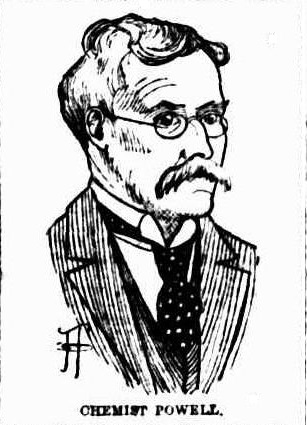

Image: Truth, 28 March 1914, p. 5

Court Artist's Sketch of Walter Powell

Walter Powell was known as an upstanding and respectable citizen. However, an assault charge in December 1913 saw his personal life revealed in salacious detail. Walter's wife Phyllis, who was described as an invalid at the time of the home invasion, died in 1911 and in 1912 he began courting Evelyn Solomon, a wealthy widow from Brunswick. Walter visited Evelyn regularly, sometimes staying overnight, and wrote her romantic letters. They were engaged to be married and a condition of their marriage was that Evelyn would pay Walter £1,000 and they would make wills nominating each other as beneficiaries. But the path to true love is not always smooth. Walter reneged on his marriage proposal and in December 1913 he was charged with assaulting Evelyn at her home in Brunswick. During court proceedings, scandalous allegations were made against Evelyn, including a claim that she had given Walter "a loathsome disease". The tabloid newspaper Truth made much of these allegations, claiming that Walter's main defence was to vilify Evelyn's character. Walter Powell was found not guilty of assault causing actual bodily harm, but guilty of the lesser charge of common assault. On this charge, he was fined £20 and placed on a bond of £50, with a surety of £50, to keep the peace for twelve months.10,11

For the remainder of his life Walter Powell stayed mostly on the right side of the law, apart from a couple of minor convictions. In July 1925, Powell and fellow chemist Samuel Knipe were each fined in Carlton Court for failing to close their shops after 1.00 pm on a Saturday afternoon. Powell, possibly mindful of reputational damage, entered a plea on the ground that the charge was "merely a technical error" and he, as a chemist, he was often called on to dispense prescriptions after hours. However, in this case the purchase was a toothbrush, not life-saving medicine. Powell offered to donate £1 to the poor box in lieu of a fine, but the magistrate upheld the original charge and fined him the equivalent amount of 20 shillings, plus 15 shillings costs. The second case, a month later in August 1925, also involved Samuel Knipe for breaches of the Dangerous Drugs regulations. George Edward Bate, who appeared as a witness in court, was no ordinary customer – he was an inspector employed by the Pharmacy Board. He gave evidence that, on separate occasions, Knipe and Powell had dispensed prescriptions for eye drops (containing a narcotic) more than once on the same prescription. Each chemist was fined 20 shillings, with £3, 3 shillings costs. Walter Powell died at Hopetoun House in October 1927 and was buried at Boroondara Cemetery in Kew. His estate was valued, for probate purposes, at £2,828, 14 shillings and 2 pence, with the proceeds going to his surviving children and grandchildren. His daughter Sophia, to whom Walter bequeathed his piano, placed memorial notices to her father in newspapers from 1927 to 1951 inclusive.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19

The next chemist to take over Walter Powell's business was Hugh Ellis Webster. He was born in the Melbourne suburb of Camberwell in 1893 and in 1916, at the age of 23, he enlisted in the AIF (Australian Imperial Force). According to his attestation paper, his occupation was "chemist" and he had completed four years of an apprenticeship with A.H. Heath of Camberwell. Webster was assigned to the 14th Australian General Hospital unit and he served overseas for the remainder of World War 1. After his return to Australia, he passed his final Pharmacy Board exam in March 1921 and was registered a month later in April 1921. He married Doris Ada Busch in November 1922 and they had two sons – Edgar Grover born in November 1923 and Hugh Ellis junior born in July 1925. In 1927, the year of Walter Powell's death, Webster was working at the U.F.S. (United Friendly Societies) dispensary in Port Melbourne. By 1928 the electoral roll lists Hugh and Doris Webster at 781 Nicholson Street, North Carlton. They were still in residence above the chemist shop in Nicholson Street when Hugh died suddenly on 5 August 1951. Hugh Webster was cremated and his ashes were interred at Springvale Botanical Cemetery. He owned no real estate at the time of his death – the chemist shop and residence was owned by Helen Thompson (neé Telfer) – and his entire personal estate, valued at £2,086, 3 shillings and 2 pence, went to his widow Doris. Probate was granted to his sons, Edgar and Hugh, both of whom worked in the insurance industry.20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27

The third chemist in the trilogy was Ian Alexander Reilly. He passed his final Pharmacy Board exam in December 1945 and was registered in August 1946. Reilly's address was registered at 781 Rathdowne Street from January 1952 to May 1976 inclusive. In the 1980s, Hopetoun House was occupied by a picture framer and gallery until 2023 when, in a complete change of business, "The Fishmonger's Son" moved upstream from 703 to 781 Nicholson Street.28

Notes and References:

1 Building ownership and occupancy information has been sourced from land titles, Sands & McDougall directories and Melbourne City Council rate books.

2 1871 England Census; Class: RG10; Piece: 2521; Folio: 12; Page: 16; GSU roll: 835251

3 Pharmaceutical Register, Certificate no. 859, 9 March 1887

4 The Herald, 4 January 1895, p. 2

5 The Argus, 7 March 1895, p. 6

6 The Age, 26 July 1901, p. 6

7 The Herald, 6 May 1902, p. 2

8 The Age, 18 June 1902, p.

9 The Argus, 28 July 1904, p. 8

10 The Argus, 20 April 1911, p. 1

11 Truth, 28 March 1914, p. 5

12 The Age, 22 July 1925, p. 19

13 The Argus, 26 August 1925, p. 7

14 Samuel Horace Knipe (certificate no. 1380) lived at several different addresses in North Carlton. He was living at 868 Rathdowne Street

at the time of the 1925 court case.

15 Death reg. no. 13706/1927

16 Boroondara Cemetery records

17 Walter Powell Probate (VPRS 28/P0003, 218/136)

18 Walter Powell Will (VPRS 7591/P0002, 218/136)

19 The Argus, 6 August 1951, p. 15

20 NAA: B2455, WEBSTER HUGH ELLIS

21 Pharmaceutical Register, Certificate no. 1947, 13 April 1921

22 The Argus, 21 December 1922, p.1

23 Birth reg. no. 33068/1923

24 https://www.findagrave.com/

25 The Argus, 6 August 1951, p. 15

26 Springvale Botanical Cemetery records

27 Hugh Ellis Webster Probate (VPRS 28/P0004, 441/273)

28 Pharmaceutical Register, Certificate no. 3835, 14 August 1946

The Flock Factory

Photographer: Charles Nettleton

Digitised Image: State Library of Victoria

Carlton looking east towards Cardigan and Lygon streets in 1870

The flock factory is the large building with the domed roof, to the left of the Builder's Arms Hotel

In the early decades of Carlton, there were no mandatory planning or building regulations in place. The provisions of the "Act for regulating buildings and party walls and for preventing mischiefs by fire in the City of Melbourne", commonly called the Melbourne Building Act (1849), did not apply north of Victoria Street until the 1870s. In this largely unregulated environment, Carlton developed as a mix of houses, shops and factories, often in close proximity. One such building was a flock factory, operated by Allan Kinsley Tronson and James Hill, on the western side of Lygon Street, south of Queensberry Street. In 1864, Tronson & Hill took over James McKenzie's coffee and spice grinding factory, which had operated on the site since 1855. The land, one of six crown allotments in the block bounded by Lygon, Queensberry and Cardigan streets, was granted to Frederick Griffin in 1853. Under leasing arrangements, the lessee could build and retain ownership of structures on the site, and houses of predominantly timber construction had been built in the immediate surroundings. Flock was in demand in Victorian times, for embellishing decorative wallpapers and, at the lower end of the production scale, textile waste was processed as shoddy, for use as mattress and furniture stuffing. Tronson & Hill received an "excellence of manufacture" award for its woollen flocks and shoddy in the Inter-Colonial Exhibition of 1866-67. The word "shoddy" clearly had a different meaning in the flock industry, compared to the derogatory term in use today.1,2,3

The flock manufacturing process, while not as hazardous as some industries, involved the use of machinery for shredding and processing textile materials, and carried the added risk of airborne dust and fluff. In December 1866, there was an accident at the factory which, according to different newspaper reports, was either "slight" or "serious". Damage to the machinery was estimated at £50, but fortunately there were no injuries to the workers. A year and five months later, in May 1868, two Tronson & Hill workers – Louise and Dennis Lynch – died in tragic circumstances. Allan Tronson gave evidence at the inquest on 18 May and confirmed that three members of the family – Ann Lynch and her adult children – were employed at the factory and were paid piece work rates. He considered that they could have earned more money if they applied themselves to the job. Louise was the most efficient of the three workers and she could earn 15 shillings a week, while the combined family income was only about 20 shillings. Mr Tronson stated that he had no idea that the family was in such distress and he assumed that Louise was in receipt of an allowance. Louise was a single mother with two small children and she received no support from the father William Fowler, a theatre worker, who was away in India. She was the main breadwinner for the family and had to take the children to work with her, a practice that would not be allowed in factories these days. Her mother Ann, a widow, was often the worse for drink and her younger brother Dennis was not much help. Dennis came to work one day, at the behest of his mother, but he was sent home because he was obviously ill. He never returned and he was dead within the week. The police and a doctor went to the Lynch family home on Friday 16 May and they were shocked by the squalid conditions in the two-roomed house, off Madeline Street. Louise and Dennis were near death, and their mother Ann was in a drunken state. The brother and sister were taken to hospital, while arrangements were made for the care of Louise's children and Ann was taken to the watchhouse to sober up. Louise died in the early hours of Saturday morning and her brother Dennis lingered on for another day. The cause of death, originally thought to be from starvation, was found to be typhoid fever, a bacterial disease commonly associated with conditions of poor hygiene and sanitation.4,5,6,7,8

1869 was a momentous year, in which the flock factory was destroyed by fire and two people close to Allan Tronson died. Around midnight on 6 August, a fire broke out and, fuelled by combustible materials stored on the premises, quickly engulfed the building. The glow from the fire lit up the night sky and attracted a large number of spectators. The fire soon spread to the nearby timber houses in Clare Place (off Lygon Street) and Hotham Place (off Cardigan Street and backing onto the factory). Built with inadequate fire protection, one house after another succumbed to the flames. Most of the occupants were asleep at the time but, by some miracle, they were able to escape and there were no casualties. As the new day dawned, the full extent of the devastation emerged. The flock factory was a smouldering ruin and sixteen working class families were homeless. The rental properties in Clare and Hotham places were insured, but there was no insurance cover for the tenants' furniture and personal property, most of which was lost or damaged in the fire. The Carlton Fire Relief Committee was promptly established to collect and distribute public donations to compensate the tenants for their losses. The situation was different with the flock factory. The business was valued at £3,000, but insured for less than half the value. In the immediate aftermath of the fire, The Herald published a statement that on 25 July Richard Fraser Tronson, Allan Tronson's half brother, "… went down on his knees and prayed fervently that his brother's place might he burned down and that his business might be ruined". Richard categorically denied the claim, but a whiff of conspiracy lingered on. Just one week after the fire, the business partnership between Allan Kinsley Tronson and James Hill was dissolved by mutual consent. The agreement, dated 12 August 1869, was published the following day in newspapers, together with a notice advising settlement of outstanding accounts. The timing seems extraordinary, however the business decision may have been made before the fire and the public notice of dissolution was simply a formality. There was a possibility that Mr Hill left the business for health reasons. James Hill signed his last will and testament on 7 September 1869, the same day he died at his home in Berkeley Street, Carlton, aged 32 years. In his deathbed will, he named William Gill (merchant) and Allan Tronson (flock manufacturer) as executors, trustees, and guardians of his young son Walter Hill.9,10,11,12,13,14,15

Meanwhile local residents, who had witnessed the devastation of the fire, were not happy. They petitioned against the re-establishment of the flock factory, on account of the dust and effluvia emanating from it, and the injurious affect on their health. Councillor McPherson gave notice of motion to the effect that the Governor-in-Council should allow a by-law to be passed, extending the present Melbourne Building Act to Carlton. This was not actioned until a few years later and, in the interim, unregulated building construction continued. The cottages of Hotham Place were rebuilt in brick and the street was renamed Ievers Place. Allan Tronson had a new business partner, Joseph Rutherford, and under their direction, the flock factory rose like a phoenix from the ashes. Tenders were advertised in September and October 1869 for building and repair of equipment and, by the time Charles Nettleton took the photo in 1870, the new factory dominated Lygon Street. As the year drew to a close, Allan Tronson's half brother Richard – the man who had allegedly prayed for his business to burn down – died in November 1869. Richard, who was drunk at the time, was hit by a horse-drawn cab and taken to hospital. His right leg was so badly broken that amputation was the only viable treatment option and, with the limited infection control procedures in place at the time, gangrene soon set in. Richard Tronson died a few days later and the cause of death was a compound fracture of the leg, gangrene and delirium tremens. Once again, Allan Tronson was called to give evidence at the inquest, which was held at the hospital on 9 November. He stated that Richard Fraser Tronson, aged about 46 years, was his half brother. Richard had served in the army in India and had arrived in Australia about four years ago, where he had led a disreputable life. Twice, in May and June of 1868, he was brought before the court on charges of drunkenness. He was a grocer and spirit merchant by trade, but he was better known on the streets of Melbourne as a vendor of songs.16,17,18,19,20,21

With production capacity restored after the fire, the factory in Lygon Street continued to operate for the next thirty years. In November 1882, fire broke out in a flock chute at the factory but, unlike the fire of 1869, it was quickly brought under control by the workers. However the damage, estimated at £150, was not covered by insurance. Allan Kinsley Tronson, the original partner of the flock business, died at his home in Drummond Street, Carlton, on 18 Nov 1884. He was 50 years old. Probate was granted to John Davies and William Simpson, as executors of his estate, and in March 1885 Tronson's share of the business was sold to Joseph Rutherford. Frederick Griffin, the original land owner, died in England in 1885 and probate was granted to G. Fitzmaurice. Griffin's extensive real estate inventory included a four-roomed cottage on the factory site, the property of the deceased, and all other "removable" buildings were the property of the lessees. In May 1890 there was another fatality involving a worker employed at the factory. Alfred Cecil Loder, an engine-driver, was using a grindstone when his left hand was caught and crushed in the machinery. The hand had to be amputated but, unlike the case of Richard Tronson's broken leg, the stump was healing well. However, Loder contracted pneumonia and died in hospital. He had no known relatives in Victoria and left behind his fiancée, Elizabeth English. William Rutherford, foreman, gave evidence at the inquest in June 1890. He stated that the accident could have been prevented if Loder had used a clamp, instead of his hand, to hold the machinery in place. Loder had a history of drunkenness, though not in recent years. The coroner ruled that the cause of Loder's death was acute pneumonia and not as a result of the hand injury. Rutherford's safety record was in the clear.22,23,24,25,26,27

Two years later, in 1892, there was a spate of burglaries in Melbourne and the flock factory was one of its intended victims. On Friday 30 September, at the close of business, Joseph Rutherford locked up the factory and office, as per usual. When he arrived the following morning, he found that the side door to the building had been forced and the office was in a state of disarray. Items had been removed from around the iron safe, possibly with the intention of taking it away or blowing it open. However, it seems that Mr Rutherford had outsmarted the would-be burglars. After a previous burglary, he placed a notice on the safe stating: "This safe is empty and contains books only". The burglars, who were obviously literate, took him at his word and abandoned their nefarious quest. Joseph Rutherford died at his home in Elgin Street, Carlton, on 15 October 1899. He was 77 years old and had outlived his fellow flock manufacturers Allan Tronson and James Hill. The death of Rutherford also marked the end of the flock factory, after 35 years of operation. Rutherford's probate documents included a detailed inventory of plant, equipment and materials, including bales of shoddy in various grades and colours. The estate was valued at £7,228 6 shillings and 10 pence and his housekeeper, Eliza Jones, received the generous amount of £500 "for her faithful services". The residue of the estate was divided equally between the Bendigo Hospital, Melbourne Hospital, Austin Hospital for Incurables, Women's Hospital and Melbourne Hospital for Sick Children (both in Carlton).28,29,30,31

When the last trace of flock and shoddy had been cleared out, the factory at 53-55 Lygon Street was taken over by the Melbourne Glass Bevelling & Silvering Company. The factory site was acquired by the Government of Victoria in 1977 and, together with the surrounding properties acquired in 1980, was redeveloped as R.M.I.T.'s Carlton campus. Ievers Place (née Hotham Place) was acquired by Davies, Coop & Company Pty Ltd in 1934 and the "ramshackle old cottages" were demolished to make way for a new cotton finishing mill. Building regulations had changed since the early days and, to assist in slum clearance, the Melbourne City Council allowed the company to build across the dead-end laneway, thus shortening the already-short street. Apart from the street sign, all that remains of Ievers Place is the laneway entrance, immediately north of Mary's Terrace at 50-56 Cardigan Street.32,33

References

1 Act for regulating buildings and party walls and for preventing mischiefs by fire in the City of Melbourne, No. XXXIX, 12 October 1949

2 Land ownership and occupancy information has been sourced from land title records, Melbourne City Council rate books and Sands & McDougall directories.

3 The Argus, 14 February 1867, p. 1 supplement

4 The Argus, 18 December 1866, p. 4

5 The Age, 18 December 1866, p. 5

6 Louise Lynch: Inquest (VPRS 24/P0000, 1868/152 Female)

7 Dennis Lynch: Inquest (VPRS 24/P0000, 1868/438 Male)

8 Typhoid fever, also known as "colonial fever", is a bacterial disease caused by Salmonella typhi.

The disease can now be treated with antibiotics and cases are rare in Australia and other developed countries.

In May 1868, the month in which Louise and Dennis Lynch died, the Registrar-General on the vital statistics of Melbourne and suburbs noted a large increase

in the number of deaths from scarlatina (scarlet fever), diptheria, croup, typhoid fever, and phthisis (tuberculosis), as compared with the previous month.

(The Argus, 1 July 1868, p. 5)

9 The fire was first reported in newspapers on 6 August 1869.

10 The Argus, 7 August 1869, p. 5

11 The Herald, 6 August 1869, p. 3

12 The Herald, 16 August 1869, p. 2

13 The Argus, 13 August 1869, p. 3

14 James Hill: Grant of probate : Date of grant : 11 Nov 1869 : Date of death : 7 Sep 1869 (VPRS 28/P0001, 7/775)

15 James Hill: Will : To whom committed : A. K. Tronson (VPRS 7591/P0001, 7/775)

16 The Argus, 23 August 1869, p. 4

17 The Age, 23 August 1869, p. 2

18 The Argus, 4 September 1869, p. 6

19 The Argus, 9 October 1869, p. 3

21 Richard Fraser Howson [sic]: Inquest : Cause of death : Accidentally knocked down by a cab (VPRS 24/P0000, 1869/917 Male)

Note: Richard Fraser Tronson's inquest report is incorrectly recorded under the surname "Howson".

22 The Age, 18 November 1882, p. 5

23 Allan K. Tronson: Grant of probate To whom committed : J. A. Davies and W. T. Simpson :

Date of grant: 18 Dec 1884 : Date of death: 18 Nov 1884 (VPRS 28/P0001, 28/827)

24 Allan Kinsley Tronson lived at 2 Louisa Terrace, Drummond Street, on the corner of Queensberry Street.

25 The Argus, 2 March 1885, p. 7

26 Frederick Griffin: Grant of administration : To whom committed : G. Fitzmaurice : Date of grant: 6 May 1886 : Date of death: 8 Jul 1885

(VPRS 28/P0002, 32/846)

27 Alfred Cecil Loder (Loader): Inquest : Cause of death : Pneumonia : Date of hearing: 10 Jun 1890 (VPRS 24/P0000, 1890/818)

28 The Herald, 1 October 1892, p. 1

29 Joseph Rutherford: Grant of probate : Date of grant: 15 Dec 1899 : Date of death: 15 Oct 1899 (VPRS 28/P0002, 73/429)

30 Joseph Rutherford: Will : Grant of probate : Date of grant: 15 Dec 1899 : Date of death: 15 Oct 1899 (VPRS 7591/P0002, 73/429)

31 Joseph Rutherford lived at Albury Terrace, 233 Elgin Street.

32 The Herald, 15 November 1934, p. 16

33 There are two small streets with the name "Ievers", most likely named after William Ievers, a well known house, land and insurance agent. Ievers Place is on the east side of Cardigan Street, between Queensberry and Earl streets.

Ievers Terrace is on the west side of Cardigan Street, opposite Argyle Square.

The Ferguson Brothers of Carlton

Source: Jewish Herald, 11 December 1908, p. 6

Newspaper advertisement for Ferguson Brothers

"Doris Street" is a typo for "Dorrit Street", where the bakehouse was located

Have you ever tasted baked goods from Ferguson Plarre bakeries? If yes, you have enjoyed the legacy of a long line of bakers who had their origins in Carlton over a century ago. This is the story of a widow, Eliza Ferguson, and her two sons, John Albert (Percy) and James Wright, who followed in their mother's footsteps to establish successful businesses in baking and catering.

Eliza Lane Crawford was born in Brandeston, Suffolk, England in 1857 and she migrated to Australia as a child in 1862. In 1878, at the age of 21, she married John Ferguson and the couple settled at Wurruk in Gippsland. Their first son John Albert, known as "Percy", was born at Sale in 1880. Tragedy struck the family in 1881. John senior, a carpenter, was working on the roof of a railway engine shed when he fell from a height of 20 feet and sustained serious concussion and internal injuries. He never regained consciousness and died the following day at Gippsland Hospital in Sale on 19 March 1881, leaving Eliza a widow with a young baby and another on the way (or "enceinté", to use Eliza's own word). Their second son, James Wright, was born in August that year. John did not leave a will and letters of administration were granted to Eliza in lieu of probate. His estate, valued at £129 2s 6d, comprised mainly three acres of land at Wurruk and a weatherboard skillion house. Eliza received a government compensation payment of £50, wages due, a collection from her husband's fellow employees, payment by the IOR Lodge – of which her husband was a member – and donations from her family and friends. Four years after her husband's death Eliza was involved in a bitter dispute with James Wright, her uncle by marriage, who had taken charge of her finances. The civil case was heard in the Sale County Court on 20 March 1885 and Eliza claimed £92 5s for money lent and rent collected on her behalf. James Wright disputed her claim and made slanderous allegations against her character. The court decided in Eliza's favour and awarded her the full amount, plus £11 14s costs. Eliza had the sympathy and support of the local community, one of whom – a Mr Baker – organised a social evening to wish her well for the future. 1,2,3,4

How Eliza managed to support herself and bring up her two young sons is not clear but, like many other widows of her time, she may have gone into domestic service. In 1899, she took over an existing pastrycook and confectionary business, previously owned by William Glenn, at 231 Lygon Street, Carlton. Her sons, John and James, who were nearing adult age, joined her in the business. The two storey shop and residence was initially a rental property owned by Thomas Pigdon and was subsequently acquired by John and James Ferguson in 1907. Eliza expanded her business by opening luncheon rooms at 54-56 Swanston Street, near St Paul's cathedral in the city. This building was the office of real estate agents and auctioneers Carney & Kelly and the luncheon rooms were most likely on the floor above. In 1900 and 1901, Eliza advertised her premises as a good vantage point for viewing street processions. She also operated the Railway Café at 270 Flinders Street, and baked goods from Carlton no doubt featured on the menu. 5,6,7,8

In April 1901 Eliza was fined 10 shillings in Carlton Court for failing to register her factory. When the Inspector of Factories and Shops visited the premises the shop manager, possibly one of the Ferguson brothers, thought that the fee of two shillings and sixpence had already been paid, but he was unable to produce the receipt. Eliza herself did not appear in court but sent a letter stating that the non-registration was due to an oversight. In the early days at Carlton, Eliza and her sons lived on the shop premises. The electoral rolls for 1903 and 1905 list John and James as bakers and, surprisingly, Eliza as "carrier". The most logical explanation is a misprint for "caterer". Two other residents, Catherine and Minnie Ferguson (both saleswomen) were listed at the same address. In 1905 Eliza married coachbuilder Henry Freeman and she moved to the Freeman family complex in Drummond Street, on the same site developed in the 1980s as Lygon Court. Her occupation was relegated to "home duties" in the electoral roll for 1906, though it is unlikely that she would have completely relinquished her involvement in the bakery and catering business. 9,10,11,12

By 1907 John and James Ferguson, now trading as Ferguson Brothers, had bought the Lygon Street shop and were registered as tenants in common. They opened a second shop at 769 Nicholson Street, North Carlton. This was a rental property and, like their mother before them, they took over an existing business run by pastrycook Mrs Edith Smith. John and James Ferguson added to their real estate holdings and production capacity in 1909, with the addition of a bakehouse in Dorrit Street and a timber building on the corner of Lygon and Waterloo streets. In December 1910, James Ferguson lodged a notice of intent to build a house in Cardigan Street, Carlton, not far from the Ferguson Brothers' bakehouse and shop. This house, "Teanville" at 212 Cardigan Street, became the new home for James and his bride Christina Coleman, who he married at St Jude's church in February 1911. They had a daughter, Marjorie Jean, who sadly died within three days of birth in May 1912. Their second daughter, Gladys Marjorie, was born in Carlton in 1914. 13,14,15,16,17

The year 1913 saw major changes for the Ferguson Brothers. The partnership was dissolved by mutual consent in April 1913 and James Wright Ferguson continued the business as Ferguson Brothers. The three Carlton properties jointly owned by the brothers were transferred to James. Christina Ferguson owned land at the far northern end of Nicholson Street, North Carlton, and in February 1913 James lodged a notice of intent to build three shops on the site. These were numbered 807 to 811 Nicholson Street and the middle shop (no. 809) became the new retail outlet for Ferguson Brothers in North Carlton. The shop's immediate neighbours were Mrs May Brown, a milliner, and Mr C.E. Taylor, a dentist specialising in vulcanite dentures. There was another pastrycook business a few doors down at no. 797 and the rental premises at no. 769 was taken over by piemaker Herbert Adams. Consumer demand must have been high to sustain three similar businesses in close proximity. Ferguson Brothers advertised regularly in the Jewish Herald and the company was granted accreditation to supply kosher products, under the supervision of an authorised shomer. 18,19,20,21,22,23,24

John Albert Ferguson was also making changes in his personal life. He married Artemisa Fortunata Maria Panelli at St Peters Eastern Hill in February 1913. Artemisa was the daughter of Italian migrants Benedetto and Teresa Panelli, and her father had a wine shop in Gertrude Street, Fitzroy. The Ferguson's first son, also named John Albert, was born in December of that year and two more sons, Alan and Robert, followed. The family lived initially at 519 Sydney Road, Brunswick, where John established his own bakery and catering business "J.A. Ferguson". The business flourished and decades later became "Ferguson Plarre", under the stewardship of the descendants of John Albert Ferguson and German immigrant Otto Plarre. John Albert Ferguson died at his home in Coburg in January 1952. His widow Artemisa died thirty years later in February 1988, at the ripe old age of 99 years. Both husband and wife were buried together at Fawkner Memorial Park. 25,26,27,28,29,30,31

James Wright Ferguson stayed in Carlton for the time being and became involved in the local community. He was appointed Justice of the Peace in the Central Bailiwick of Victoria in March 1915 – notwithstanding two minor traffic prosecutions in 1913 and 1915. In June 1914 James Ferguson made a bid for local government and stood against Carlton real estate agent Thomas Foley to fill a vacancy for Smith Ward of the Melbourne City Council. He was unsuccessful, but in February 1916 he was appointed as the sole nominee following the resignation of Thomas Foley. James served on the Melbourne City Council for the next 40 years, retiring in August 1956. He was chairman of the Markets Committee for 20 years and also chairman of the City Council's Royal Visit Committee in 1954. In recognition of his service, he was awarded the C.B.E. (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) in New Year's Honors list for 1957. His business continued to cater for private and public functions – large and small – and at times provided gratis catering services for local charities. Within the industry, James Ferguson was best known as the official caterer to the Victoria Racing Club and his busiest time was during the Melbourne spring racing carnival. In October 1930 the ovens were running hot at Dorrit Street, baking 1,000 turkeys, 150 ducks, 200 chickens, 2,000 apple pies and 4,000 dozen pastries, augmented with 500 trifles, 350 jellies, 250 fruit salads and 100 dishes of charlotte russo. 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39

By the 1920s the remaining Ferguson family members had left Carlton. Eliza and her husband Henry Freeman moved to Auburn, where she died in 1943. The Freeman family remember Eliza as a feisty woman, who drove herself everywhere in a horse-drawn carriage and made her opinions on everything well known. Henry Freeman died at his home in Glen Iris in 1946. Both were buried in Melbourne General Cemetery, Carlton. James and Christina Ferguson moved to "Questa" in Parkville, and Christina died in May 1923. Probate was granted to James, who inherited the three shops in Nicholson Street, North Carlton. "Teanville" was sold in 1924, the Nicholson Street shops in 1926, and the original Lygon Street shop in 1929, while James retained his catering business at the Dorrit Street bakehouse. James married his second wife Eleanor Maude Eileen Casey in 1925 and they lived in Brighton and later at a guest house in Macedon. The marriage ended in divorce in 1941 and James retained custody of their daughters Cynthia and Yvonne, aged 13 and 12 years at the time. He married his third wife, Sydna Delisle, in 1942. James Wright Ferguson died in Sydney in July 1974, one month short of his 93rd birthday. His widow Sydna Ferguson died in Southport, Queensland, in September 1990. 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47

The bakehouse in Dorrit Street remained in James Ferguson's ownership until the 1960s and was home to Nann's Pies from the late 1930s. The entire west side of Dorrit Street, together with parts of Cardigan and Grattan streets, were acquired by the Royal Women's Hospital from the 1950s through to the 1970s. Both the bakehouse and James Ferguson's former home in Cardigan Street were demolished to make way for the Royal Women's Hospital carpark and staff accommodation. The shop at 809 Nicholson Street has maintained a continuous connection with the aspects of baking trade, starting as a pastrycook business for Ferguson Brothers, and later as a cake shop. In the 1980s, the three shops in Nicholson Street were combined as Natural Tucker Bakery, which is still baking to this day. Eliza Ferguson's original pastrycook business at 231 Lygon Street is now a nail salon.

Notes and References:

1 Biographical information has been sourced from birth, death and marriage records, and newspaper family notices.

2 Inquest deposition file (VPRS 24/P0, 1881/235)

3 Grant of administration (VPRS 28/P0, 21/893)

4 Gippsland Times, 3 April 1885, p. 3

5 Building ownership and occupancy information has been sourced from Sands & McDougall directories, cross checked with Melbourne City Council rate books.

6 Certificates of title vol. 2602, fol. 322 and vol. 3213, fol. 555

7 The Age, 3 December 1900, p. 10

8 The Age, 23 March 1901, p. 12

9 The Herald, 26 April 1901, p. 5

10 Electoral rolls for 1903, 1905 and 1906

11 Marriage Reg. No. 5462/1905

12 Eliza and Henry Freeman lived at 335 Drummond Street, Carlton.

13 Certificates of title vol. 3329, fol. 665 and vol. 3343, fol.596

14 Australian Architectural Index, Reg. No. 2340

15 The Age, 29 April 1911, p. 7

16 The Age, 13 May 1912, p. 1

17 Death Reg. No. 29166/1914

18 The Argus, 26 April 1913, p. 12

19 Certificates of title vol. 3686, fols. 078 to 080

20 Certificate of title vol. 3620, fol. 978

21 Australian Architectural Index, Reg. No. 3897

22 Vulcanite dentures were developed in the 19th century as a more durable and elastic alternative to traditional dentures. The base was made from vulcanised rubber.

23 Jewish Herald, 21 September 1917, p. 14

24 A shomer is a guard or watchman. In the context of food preparation, the shomer ensures that all the ingredients and methods of cooking are in accordance with Jewish Law.

25 Marriage Reg. No. 388/1913

26 The Age, 20 December 1913, p. 5

27 Birth Reg. No. 1233/1919

28 For more information on John Albert (Percy) Ferguson, visit the Ferguson Plarre website

29 The Age, 21 January 1952, p. 2

30 Death Reg. No. 3278/1988. The death was registered under the given names "Maria Fortunata".

31 Fawkner Memorial Park cemetery records

32 Victoria Police Gazette, 25 March 1915, p. 314

33 The Herald, 11 April 1913, p. 1

34 The Age, 13 January 1915, p. 13

35 The Herald, 8 June 1914, p. 12

36 The Age, 2 February 1916, p. 15

37 The Argus, 1 January 1957, p. 1

38 The Advocate, 27 February 1915, p. 27

39 The Herald, 30 October 1930, p. 8

40 The Age, 20 July 1943, p. 5

41 The Age, 12 July 1946, p. 2

42 Death Reg. No. 4909/1923

43 191/139 Christina E. Ferguson: Grant of probate (VPRS 28/P3, 191/139 1923-09-08)

44 Certificates of title vol. 4778, fol. 474, vol. 3628 and vol. 3620 fol. 978.

45 1941/884 Ferguson v Ferguson: Divorce (VPRS 283/P2, 1941/884)

46 Marriage Reg. No. 17164/1942

47 Ryerson Index and NSW Death Reg. No. 9231/1974

The Salvation Army in Carlton

Image: Courtesy of Salvation Army Museum Melbourne

The Salvation Army Citadel in Drummond Street, Carlton, in the 1920s

One hundred years ago, on 18 August 1921, Commissioner James Hay opened the new Carlton Salvation Army Citadel "To the glory of God and for the salvation of the people". The distinctive brick hall was built to the same design as the Camberwell Citadel (built in 1910 and since demolished) and replaced an old double-fronted weatherboard house at 324 Drummond Street, Carlton. The Salvation Army acquired the site in December 1918, at a cost of £943, and spent an estimated £1,357 on the building. The plans were first submitted to Melbourne City Council in February 1919, but it was not until two years later in 1921 that building commenced under a new application. The location in Drummond Street was well chosen, being in the same block as the Carlton Police Station and the Carlton Court, where there were potential souls to be saved. Carlton was an economically depressed suburb in the 1920s and by the 1930s many dwellings – including whole streets – were declared unfit for human habitation. The Salvation Army played an important role in assisting the families living in poverty. Acclaimed indigenous actor, dancer and choreographer Noel Tovey was born in Carlton in 1934 and spent his early childhood years living there. In his memoir Little Black Bastard he recalls that he was taken to the Salvation Army Citadel once a year, given a new set of clothes and photographed. The studio portraits, reproduced in Tovey's memoir, depict him as a well-dressed, engaging baby and toddler – images at odds with his early life of poverty and deprivation. The Salvation Army would have helped many disadvantaged children feel special – if only for a short time.1,2,3

While the Citadel was opened in 1921, Carlton's association with the Salvation Army goes back to the 1880s, when the Army was first established in Melbourne. The salvationists made their presence felt by singing and marching in the city streets, but found themselves in breach of local regulations. In April 1883, Captain William Shepherd was fined £5, plus £5 and 5 shillings costs, for holding a procession (for other than funeral purposes) along Stephen (Exhibition) Street in the city, "without having obtained in writing the previous consent of the Mayor or Town Clerk, or having given notice to the officer in charge of the city police". Captain Shepherd was, by his own admission, a reformed prisoner who had lead a past life of sin and crime. Shepherd and his wife lived in a small cottage at 51 Lygon Street, Carlton, just a block away from the Melbourne Gaol, and he began inviting recently released prisoners to his humble home. The Salvation Army recognised the need to break the common cycle of discharged prisoners re-offending, and this lead to the formation of the Prison Gate Brigade, the first such brigade of its kind anywhere in the world. Salvation Army officers visited prisoners in the lead up to their release and waited at the "prison gate" to offer them support and accommodation to ease their transition back into civilian life. 4,5

Image: CCHG

Former Prison Gate Home at 37 Argyle Place South, Carlton

Carlton was at the forefront of the new brigade. On 8 December 1883, Major James Barker opened the Salvation Army's first prison gate home at High Ham House, 37 Argyle Place South, Carlton. The substantial two storey brick building, on the corner with Cardigan Street, was part of a terrace constructed by E. Brooke in 1873. Not all ex-prisoners stayed at the home – some were just there for meals – and not all stayed on the straight-and-narrow path to salvation, but all were accepted without judgement. The home was funded entirely by voluntary contributions of money and clothing, the latter of which was important as prisoners were often discharged with only the clothes on their backs. There was even a bootmaker and tailor in attendance to repair footwear and clothing, so that ex-prisoners would look presentable for their return to society. Around the same time, in January 1884, a home for women was opened at 11 Barkly Street, Carlton, one of a pair of cottages owned by Robert Frost. This was the first, or the forerunner, of the Salvation Army's "Fallen Sisters" or "Rescued Sisters" homes. The four roomed cottage was at least twice the size of Captain Shepherd's home in Lygon Street, and it had a bathroom, which would have been considered a luxury by many Carlton households at the time. The women's home in Barkly Street operated for a short time only, as a new home was established at Montgomery House in Gore Street, Fitzroy, in late 1884.6,7,8,9,10,11

Moving forward into the 1890s, the Salvation Army established a barracks at 62 Bouverie Street, Carlton, not far from the Carlton & West End Breweries that produced the "demon drink". The Board of Public Health approved opening of the former warehouse as a public hall in February 1891. The barracks closed four years later in February 1895. In 1915, during World War 1, the Salvation Army had a crèche built on the corner of Canning and Richardson streets, North Carlton. The crèche operated as a home for young children, rather than a day care centre, as many lived there before being placed in foster care or moved to other residential facilities. The crèche children, and also local residents, received a special treat in January 1938 when the Salvation Army distributed twenty five cases of apples from the Doncaster stores. It was quite an occasion, with Salvation Army officers beating the drum and calling on people to come out of their houses and help themselves to the free apples. Post-World War 2, the crèche was taken over by the Melbourne City Council. The original two storey crèche building was extended over the next few decades to occupy the entire corner site bounded by Canning, Richardson and Amess streets. The North Carlton Children's Centre now operates as a day care centre and kindergarten.12,13,14,15

Image: CCHG

Former Salvation Army Crèche at 481 Canning Street, North Carlton

What of the remaining Salvation Army properties in Carlton? Both Captain Shepherd's cottage in Lygon Street and the barracks in Bouverie Street have long since disappeared. The original prison gate home at 37 Argyle Place South still exists and, from external appearances, looks much the same as it would have in the 1880s. The cottage in Barkly Street, now no. 152, has had a more recent makeover, with a replacement fence and decorative iron lace on the verandah.

Notes and References:

1 The date of opening and the quotation are on the foundation stone at the front of the building.

2 Building information has been sourced from Salvation Army property records, building plans and building application files (VPRS 11200 and 11201).

3 Little black bastard : a story of survival, Noel Tovey, Hodder Headline Australia, 2004

4 The Herald, 10 April 1883, p. 2

5 The Herald, 6 April 1883, p. 3

6 The date of opening is on a commemorative plaque, on the Cardigan Street side of the building.

7 Australian Architectural Index, Record no. 77852

8 Bendigo Advertiser, 18 January 1884, p. 3

9 The cottage at 11 Barkly Street is described in the Melbourne City Council rate books, and "Mrs Russell" is listed as the main householder.

Her association with the Salvation Army is yet to be established.

10 Cox, Lindsay. Beyond prison bars, Hallelujah, vol. 3, issue 1, March 2010, p. 27

11 The Herald, 14 October 1884, p. 4

12 The Argus, 4 February 1891, p. 11

13 Salvation Army property records

14 Australian Architectural Index, Record no. 80559

15 The Age, 25 January 1938, p. 17

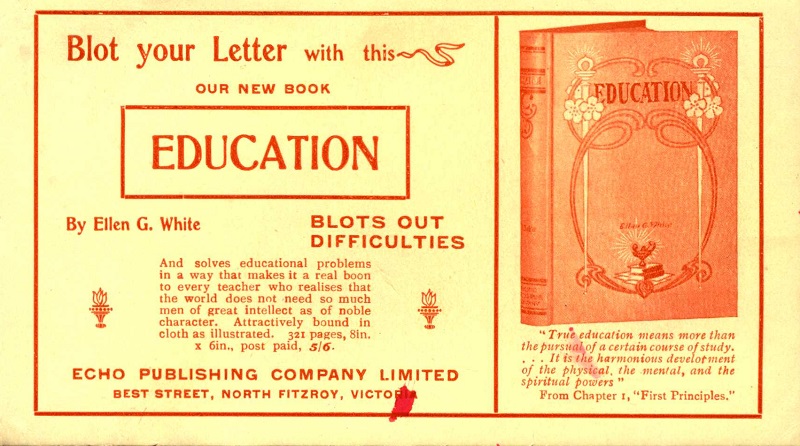

An Echo From the Past

Digitised Image: CCHG

This postcard-sized advertisement for Echo Publishing Company Limited of North Fitzroy was discovered amongst some notebooks, meticulously handwritten by William Wilson of Drummond Street, Carlton. Mr Wilson was a student at the Education Department Training College in Grattan Street, Carlton, in the early 1900s. The advertisement served a dual purpose in promoting a book by American author Ellen G. White, and the verso could also be used as a blotter – a smart way of advertising in the days of pen and ink. Ellen G. White was one of the founders of the Seventh Day Adventist movement and her book was first published by the Pacific Press Publishing Association in 1903. This places the date of the advertisement between 1903 and October 1905, when the business name of the Echo Publishing Company Limited was changed to the Signs of the Times Publishing Association Limited. 1,2

The Echo Publishing Company Limited began as a small-scale religious publisher and printer on the corner of Rae and Scotchmer Streets, North Fitzroy, in 1886. The business expanded its operations to include commercial work, and moved to larger premises at 14-16 Best Street, North Fitzroy in 1889. The Company, run by the Seventh Day Adventists, reviewed its operations in the early 1900s and made the decision, based on its religious principles, to discontinue commercial work and leave the city. This was an early example of decentralisation and involved building a new state-of-the-art factory and housing for workers and their families in Warburton, then a small village east of Melbourne. The North Fitzroy factory was vacated in February 1907.3,4,5,6,7

William Wilson's notebooks and other documents were kindly donated to CCHG by the Yarra Ranges Regional Museum. The advertising blotter is now in the local history collection of the Fitzroy Library.

Notes and References:

1 Ellen G. White Writings Website

2 Victoria Government Gazette, 4 October 1905, p. 3

3 Business address information has been sourced from Sands & McDougall directories and newspaper advertisements.

4 The Age, 30 April 1889, p. 3

5 The Age, 13 May 1905, p. 15

6 Reporter (Box Hill), 20 April 1906, p. 5

7 Table Talk, 10 January 1907, p. 24

Image: CCHG "No Parking" Sign in Canning Street, North Carlton  Image: CCHG Iron Lacework, Cnr. Canning and Macpherson Streets, North Carlton

|

Keep off the Grass

OFFENDERS PROSECUTED But are parking officers from Melbourne City Council likely to cross the municipal boundary of Princes Street to issue an infringement notice? The sign, bearing the Melbourne City Council's name and coat of arms, is a relic of times past, when Carlton, North Carlton and Princes Hill were all part of the same municipality. North Carlton and Princes Hill were hived off from Melbourne City Council and joined the newly-created City of Yarra in the 1990s. There are plenty of other reminders of Melbourne City Council to be found in North Carlton and Princes Hill. The coat of arms appears on the green street bollards and in the iron lacework of many shopfront verandahs. The images of fleece, bull, whale and sailing ship date back to 1843, when wool, tallow and oil were the chief exports of the colony (then part of New South Wales). Next time you go for a walk along Canning Street, have a look the bollards and compare the coat of arms images with those on the "no parking" sign. The whale and sailing ship images have been relocated to the lower half, while the bull has been moved up to join the fleece on the upper half. The change was made in 1970 in order to have the land-based and water-based images placed, logically, on their respective levels. Why didn't someone think of that back in 1843?1

Reference: |

Gas Lighting in Carlton | |

Image: CCHG Corner of Amess and Richardson Streets, North Carlton

Note: MMBW detail plans are available online at the State Library of Victoria's website. |

In the days before the advent of electricity, the streets of Carlton were illuminated with gas lighting. There were gas lamps on many street corners and several examples still remain, as truncated lamp post bases. The Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) detail plans, drawn up in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, include codes showing the location of gas lamps (G.L.) and electric light posts (E.L.P.). The two methods of illumination co-existed for a time, but electric lighting eventually took over and the gas lamps were decommissioned. The upper portions of the lamp posts were removed, leaving the decorative bases. There are gas lamp bases at the following locations:

Image: CCHG Corner of Nicholson and Pigdon Streets, North Carlton The lamp post was made by "D. Niven and Co., Iron Founders, Collingwood". The base was removed from the street corner in October 2019 and relocated to the opposite corner in North Fitzroy in April 2024. |

Little but Fierce

Photo: CCHG

Shakespeare Street Mural

North Carlton

The colorful mural that once faced the mini park in Shakespeare Street, North Carlton, was painted over in 2024. All that remains of this brief snapshot of Shakespeare Street's history is a small patch of orange paintwork in the far corner. The text "Little but Fierce" is taken from William Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream and was suggested by a local resident. The full wording is: "And though she be but little, she is fierce". That Shakespeare Street is "little" there is no doubt. The street is narrow and runs for one block only, between Drummond and Lygon Streets. For the "fierce" side of Shakespeare Street, we need to look back in history.

Shakespeare Street was the scene of at least two shooting incidents, one fatal, in 1922 and 1944. The street was identified as a "slum pocket" by the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board in 1936-37. The people of Shakespeare Street had a battle on their hands in the 1950s and 1960s, when the Housing Commission of Victoria condemned five cottages on the south side (nos. 7 to 15 inclusive) as unfit for human habitation. The cottages were demolished in January 1970, leaving a vacant space ready for development. Without doubt, the fiercest battle fought in Shakespeare Street was in the 1970s, against the inappropriate building of a block of cluster flats on the south side of the street. Residents and other concerned citizens took action, at their own expense, by cleaning up the vacant site and creating a mini park for the benefit and enjoyment of the community. They bravely put their money where their mouth was, so to speak, and entered into an agreement with the City of Melbourne to buy the land. Decades later, the mini park remains a tribute to the power of community action.

More information on Shakespeare Street

Related items:

Shooting in Shakespeare Street

The Penny Dreadful

The Munster Arms

Princes Street is the dividing line between Carlton and North Carlton, and a major thoroughfare for east-west traffic. When the lights turn red at the Canning Street intersection, few travellers could fail to notice the distinctive Edwardian building on the south west corner. The Dan O'Connell Hotel was a Carlton institution and perhaps best known for its St Patrick's Day celebrations. The former hotel building is over 100 years old and was designed by Smith & Ogg and built by C.F. Pittard in 1912. It was named after Irish political leader Daniel O'Connell (1775-1847), but the Irish connection goes back even further, to a earlier hotel on the same site.1

The Munster Arms Hotel, named after the province of Munster in the south of Ireland, was first licensed to Margaret McCrohan in 1875. Her application of 8 June was initially opposed, and the close proximity of two other hotels - the Pioneer hotel and United States Hotel - may have been a contributory factor. The application was postponed for 14 days and the licence was granted on 22 June 1875. The original building was described as a small brick hotel, with nine rooms, a bar and a cellar. Mrs McCrohan and her husband Eugene ran the hotel until 1881, when the licence was transferred to George Henry (Harry) Wallace.2,3,4

Wallace held the licence for about a year only, and ran into trouble when removing an unruly patron from his hotel in October 1881. He took legal action against Daniel Dorian (Dorien) for assault, but this case was dismissed by the City Bench. A few months later on 27 February 1882, Dorian, a bricklayer, sought the sum of £300, as damages for an assault and battery, and malicious prosecution. The civil case was heard in the Supreme Court before a judge and jury. The presentation of evidence from both parties took the greater part of the day and the judge commented that the case could have been dealt with in a lower court. After a short deliberation by the jury, Dorian, the plaintiff, was awarded £5, considerably less then the desired amount.5

By the end of the month, George Henry Wallace had transferred his licence to Annie McCanny. Mrs McCanny, former licensee of the Kensington Hotel, did not have the capital to finance her new hotel business and she entered into an arrangement, to the value of £396, with the Melbourne Brewing and Malting Company Limited. Such financial arrangements were common in the nineteenth century and enabled persons of limited financial means to go into business. The brewing company acted as a de facto bank and the hotel was "tied" to the company and required to sell its beer. The bill of sale between Annie McCanny and the Melbourne Brewing and Malting Company Limited, dated 30 March 1882, includes a detailed room-by-room inventory of the hotel contents, and this gives a fascinating snapshot of the hotel in the 1880s.6