Names are more than just words. They give us a sense of identity and locality, and commemorate cultural and historical connections. Carlton has a rich history of names - from the names that appear on the parapets of individual houses or groups of houses in a terrace, through to laneways, streets, parks, and the suburb itself. Naming conventions are now strictly regulated, with significant rules that a place should not be named after a living person or an existing business or organisation, and that duplication of names should be avoided. It was a different situation in the 19th century. In the early days of Carlton, streets were routinely named after British dignitaries and prominent citizens. A few decades on, in the 1870s and 1880s, Melbourne City councillors were rewarded with street names upon their retirement. John Curtain, Member of Parliament and Melbourne City Councillor, had both the reserve know as Curtain Square and the adjacent street named after him.1,2,3

House names open up a whole new area of naming rights. Some houses, such as Westray Villa in Canning Street, have a demonstrated connection with the original owner, while others were named at the whim of the builder. Themes are common for a row of houses by the same builder: Floral themes such as "Daphne, Violet and Pansy" and the shipping themes "Suevic, Afric and Runic". Houses were sometimes named after the street in which they were built and, as the house names were not regulated, there was some duplication within the same suburb. For example, there was once a short street named Rathdowne Terrace off the southern end of Rathdowne Street, and a more substantial terrace of three double storey houses, with the same name, just a few blocks away.

The origins of many of these names have been lost in history and are often the subject of speculation. Carlton Community History Group acknowledges the importance of place and house names as part of our heritage and we are documenting these from available sources. Contact us if you can contribute to this important line of research.

Notes and References:

1 Naming rules for places in Victoria : Statutory requirements for naming roads, features

and localities. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2016

2 Street Names

3 The Age, 25 April 1876, p. 3

A Man of Colours

Walter Renny and Royal Blue Terrace

Image: CCHG

Royal Blue Terrace

233 to 237 Rathdowne Street Carlton

The colour blue is found everywhere in nature – the sea and sky, mountains in the distance, plants and flowers – and is often associated with royalty, aristocracy and the flags of nations. Blue was of special significance to Walter Renny, a colourful character and the original owner of Royal Blue Terrace in Rathdowne Street, Carlton. Walter Renny, a master painter and decorator, was born in England and migrated to the Colony of New South Wales in 1853. He settled in Sydney and married Mary Ann White at Balmain in 1857. Renny established a business in Pitt Street, Sydney, and advertised his calling by decorating his premises with blocks of blue and white. The building became known as the "Royal Blue House" and earned its master the nickname of "Royal Blue Renny". Walter Renny was also active in local government, serving as alderman for the City of Sydney from December 1863 to November 1865, and December 1866 to 30 November 1870. Renny was elected Lord Mayor of Sydney in 1869-70. He stood for the Legislative Assembly in a by-election for the seat of East Sydney in 1867, but his bid was unsuccessful. Preliminary advertisements for the sale of his residence "Strathfieldsaye" first appeared in Sydney newspapers in December 1871, stating that Walter Renny was leaving the colony for health reasons. His final departure from Sydney was announced two years later in Sydney Punch in December 1873.1,2,3

Walter Renny moved south to Melbourne and purchased land in Rathdowne Street, in a prime location opposite the Carlton Gardens, in 1874. The land was originally part of a government grant to the Erskine Church, on the corner of Rathdowne and Grattan streets, and was subdivided for sale under the provisions of the State Aid to Religion Abolition Act (391/1871). An invitation for tenders for the erection of a terrace for Walter Renny was advertised in The Argus in April 1874. The contract was awarded to James Lever, who built the three adjoining double storey houses, designed by Crouch & Wilson. In keeping with Walter Renny's colour theme, the terrace was named "Royal Blue Terrace". Renny and his wife Mary Ann took up residence in the first house in the terrace (now no. 233 Rathdowne Street) and the remaining two houses (nos. 235 and 237) were rented out. In October 1875 the Renny residence was the scene of an audacious daylight robbery, in which household and personal items valued at over £200 were stolen. There was nobody at home on the afternoon of 5 October and the thief or thieves gained entry, police believed, with a skeleton key. The haul, as detailed in the Victoria Police Gazette, included a small six-barrelled revolver, a silver tea service and a silver cigar case, both engraved and presented to Walter Renny when he lived in Sydney. In a surprising turn of events, a large sack containing some of the lesser-value stolen items was found a week later in the backyard of a house in Eastern Hill. The following year, in July 1876, Walter Renny was appointed Justice of the Peace for the Central Bailiwick of Victoria.4,5,6,7,8

In April 1878 Walter Renny embarked on an overseas trip and, as fate would have it, he would never return to Australia. After spending time in Italy, he became ill in Paris and, as his condition worsened, he was transferred to his mother's residence at Forest Gate in London. He died there on 24 June 1878, aged 49 years. The reported cause of death was "congestion of the lungs", though The Gundagai Times stated he had contracted typhus fever. While Walter Renny died in England, he owned real estate and personal property in Australia and his estate was subject to local probate. The houses of Royal Blue Terrace were valued at £3,000, and probate was granted to Richard Thomas Hills and Harry Ward. Ownership changed several times over the next seventy years, when Royal Blue Terrace was subdivided and the three houses were sold separately in the late 1940s. Royal Blue Terrace and its neighbour "Loch-Shin House" at 239 Rathdowne Street are now the only surviving 1870s buildings in the block between Pelham and Grattan streets. The original 1860s Erskine Church, on the Grattan Street corner, was rebuilt in the 1870s, then demolished in 1971. State School 2605, now Carlton Gardens Primary School, was opened in 1884, and the Sacred Heart Church, on the Pelham Street corner, was built from 1897 to 1899. Walter Renny's legacy of Royal Blue Terrace is now well into its second century.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16

Notes and References:

1 McCormack, Terri. Renny, Walter. Dictionary of Sydney, 2012

2 Sydney Morning Herald, 25 December 1871, p. 7

3 Sydney Punch, 12 December 1873, p. 3

4 Certificate of Title, volume 699, folio 636

5 Australian Architectural Index, record nos. 27272 and 77950

6 Victoria Police Gazette, 5 October 1875

7 The Herald, 13 October 1875, p. 2

8 Victoria Government Gazette, 48, 14 July 1876, p. 281

9 The Argus, 13 August 1878, p. 1

10 The Gundagai Times, 30 August 1878, p. 4

11 18/062 Walter Renny: Grant of probate (VPRS 28/P0000, 18/062)

12 Certificate of Title, volume 3427, folio 367

13 Erskine Presbyterian Church, Centenary 1850-1950

14 Demolition Permit D3373, 20 September 1971 (VPRS 17292)

15 Victorian Heritage Register H1624

16 Victorian Heritage Register H0016

Station Street North Carlton

What Station?

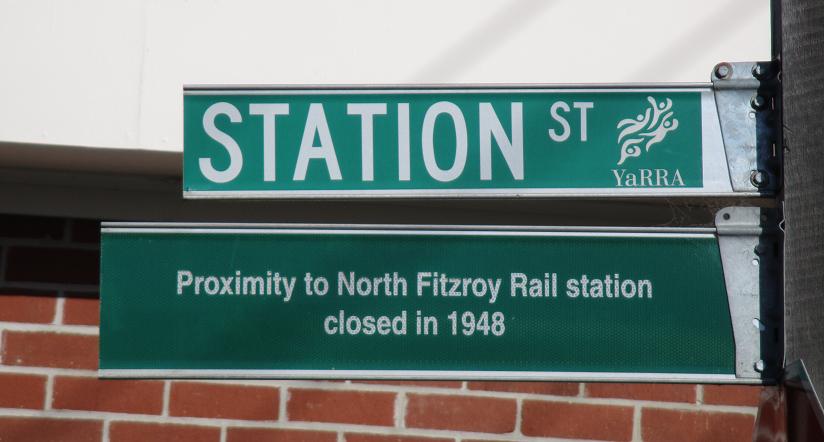

Street sign on the corner of Station and Park streets, North Carlton

"Station" is one of the more popular street names in Melbourne and is most likely associated with the location of a railway station, past or present. City of Yarra has taken this approach in attributing the name of Station Street in North Carlton to its proximity to the former North Fitzroy railway station, which was east of Nicholson Street in North Fitzroy. The street sign cites the date of 1948 when the railway line closed to passenger traffic, but not the opening date, and this omission provides a vital clue that the name attribution cannot be correct.

When the inner circle railway opened in May 1888, North Carlton was a rapidly developing suburb north of Princes Street. The situation was very different in the 1850s, when the main north-south streets of Carlton were being laid out. Station Street appears on a plan of Carlton allotments dated 1859, a decade before the suburb of North Carlton was created and nearly three decades before the inner circle railway line was opened. So how did Station Street get its name? The same 1859 plan shows the area between the Carlton Gardens and the intersection of Neill and Nicholson streets divided into allotments, earmarked for real estate development. However, the land bounded by Station, Nicholson and Elgin streets was designated for a different purpose and bears the annotation "Land set apart for Yan Yean Tramway Terminus". This raises the question of a connection between the inner suburb of Carlton and the rural area of Yan Yean. The answer lies in the early history of Melbourne's water supply and the major infrastructure project that brought water from Yan Yean to Melbourne.1

In the early days, the city's water supply was precarious, particularly during the summer months. Rainwater had to be collected, bores were sunk and water was pumped and carted from the Yarra River and other water courses. As the town's population grew, so did the demand for water and the only long term solution was to construct a reservoir to hold water and convey it via a system of pipes to the city. Yan Yean, north east of Melbourne, was chosen as a suitable site, with water drawn from the Plenty River. Construction took place over four years, from December 1853 to December 1857, and it was a major engineering project for its time. The cast iron water pipes from the reservoir were laid through bushland to the outskirts of Melbourne, then followed the course of what later became St Georges Road to join Nicholson Street near Yorke (later Lee) Street and thence to the Carlton Gardens.2

Melbourne had its first taste of Yan Yean water on 31 December 1857, when the main valve was opened at the Carlton Gardens and water jets spouted at various locations in the city. With the project completed there was the matter of what to do with the miles of wooden tramway that had been built between Yan Yean and Melbourne to aid pipe laying. Engineer Matthew Bullock Jackson proposed that the tramway could be converted into a locomotive railway line, with iron rails, for carrying goods and passengers. This would open up Yan Yean and locations along the way to settlement and sightseeing traffic. It was a bold idea and no doubt Jackson had the engineering skill and ability to make it happen, but funding was lacking and the project never went ahead. The land was released for sale in 1863 and a plan of allotments for the same year shows real estate blocks in place of the Yan Yean tramway terminus.3

On the balance of evidence the Yan Yean tramway, which never opened as a railway line, has a greater claim to the naming of Station Street than the inner circle railway line that opened decades later. The North Fitzroy railway station has long since disappeared, but the former North Carlton station remains further west in Princes Hill. It is now a neighbour house.4

Postscript: The North Fitzroy rail station signage was removed in July 2022.

References:

1 Plan of allotments at Carlton, North Melbourne, Parish of Jika Jika. Public Lands Office Melbourne, August 3rd 1859

2 Dingle, Tony and Doyle, Helen. Yan Yean : A history of Melbourne's early water supply. PROV, 2003

3 Plan of allotments at Carlton, North Melbourne, Parish of Jika Jika. Public Lands Office Melbourne, September 3rd 1863

4 Atkinson, Jeff. The inner circle line : The Melbourne suburban rail line that disappeared. Carlton Community History Group, 2021.

A Street Named Madeline

Photographer: Charles Nettleton

Digitised Image: State Library of Victoria

Madeline Street Carlton, looking north towards Grattan Street in 1870

Carlton was originally developed as a northern extension of the City of Melbourne. Early maps show the now-familiar street names, with a few exceptions. Most notable is "Madeline Street", which ran in a northerly direction from Victoria Street, through Carlton to its intersection with Keppel Street. Madeline Street kept its name for over 70 years, when local opinion favoured its renaming as a continuation of Swanston Street in the city.1,2

In September 1924, Councillor Campbell presented a petition signed by 368 property owners and ratepayers of Smith Ward, requesting that the name of Madeline Street be changed to Swanston Street:

Cr. Campbell explained that Madeline-street, which joined Swanston-street at Victoria-street, was really a continuation of Swanston-street. The City Baths were at the end of Swanston-street, but were actually in a straight line with Madeline-street. The city was growing northwards, and it was really time that Madeline-street was regarded as part of Swanston-street, of which it was the natural continuance.3

The petition was referred to the Public Works Committee and the name change was approved by Council in March 1925. Like any change, it took a while to runs its course. Properties along the full length of the street, from Victoria through to Keppel, had to be re-numbered to a new sequence from the 400s to the 800s. Maps and street signs had to be changed, while businesses and residents who used personalised stationery headed off to the printers.4

Did the City of Melbourne make the right decision in duplicating the name "Swanston Street" in Carlton? The Melbourne metropolis was expanding in all directions and by the end of the 1920s there were calls for a co-ordinated approach to street naming and numbering. In 1929, there were reportedly five streets named "Swanston" in Melbourne, and Post Office Place in Carlton and Park Street in North Carlton were cited as examples of street name duplication. However, the goal of having a unique name for every street in Melbourne was never achieved.5,6

The old name "Madeline Street" still had its uses. In April 1934, an abandoned baby girl was found outside the Women's Hospital in Carlton. She was named "Madeline Carlton", after the location where she was found, and committed by the Children's Court to the care of Berry Street Foundling Home until her future was decided. A few months later, in September 1934, The Herald, reported that "Madeline" had been adopted out. In this case, it was quite appropriate to use the old street name, as "Swanston" was hardly a name choice for a baby girl.

References

1 Plan of the City of Melbourne and its extension northwards (1852)

2 Plan of the extension of Melbourne called Carlton (1853)

3 The Age, 30 September 1924, p. 10

4 The Age, 3 March 1925, p. 10

5 The Herald, 12 November 1929, p. 6

6 The Herald, 26 July 1929, p. 11

7 The Herald, 12 April 1934, p. 1

8 The Herald, 18 September 1934, p. 1

Rosh Pinah

From Palestine to Princes Hill

Image: CCHG

Rosh Pinah

311 Pigdon Street Princes Hill (Cnr. Arnold Street)

Rosh Pinah, the corner block of flats at 311 Pigdon Street, Princes Hill, was designed by Archibald Ikin and built in 1940 for Norman and Rosa Shnider. The name "Rosh Pinah", which means "cornerstone" in the Hebrew language, is taken from Norman Shnider's birthplace of Rosh Pinah in Palestine. Norman was born there on 22 August 1903 and he migrated to Australia as a child in August 1914. The block of flats has a heritage listing and is described thus:

"The Rosh Pinah flat block is significant as a large two-storey stuccoed building set on a corner site, with parapeted and hipped terra-cotta clad roofs, steel framed windows, bold curved architectural forms, original fence – all designed in the Moderne style. Rosh Pinah also represents the Jewish presence in North Carlton and adjacent areas, as an early phase of modern European emigration into Melbourne in the 1930s." 1,2,3,4

Rosh Pinah features in Robert Gott's crime novel The Port Fairy Murders, published by Scribe in 2015. One of the characters, Joe Sable, a police sergeant with the Homicide Department, is living in an upstairs flat at Rosh Pinah in 1944. The young man, Jewish by birth but not by practice, is still suffering mentally and physically from a recent encounter with his nemesis, the vengeful George Starling. As the action moves between Melbourne and Port Fairy, a coastal town in the Western District, the body count rises. Someone dies at Rosh Pinah, but what is the connection – if any – with George Starling? Read the book to find out.5

Notes and References:

1 Building ownership information has been sourced from Melbourne City Council rate books for Victoria ward.

2 Alien registration file of Norman Shnider (NAA: B6531, NATURALISED/1939-1945/SHNIDER NORMAN)

3 City of Yarra Review of Heritage Precincts, 2007. Appendix 7, p. 413-414

4 The original building had exposed brickwork until the late 1960s.

5 The Port Fairy Murders is available, in print and e-book format, at Yarra Libraries.

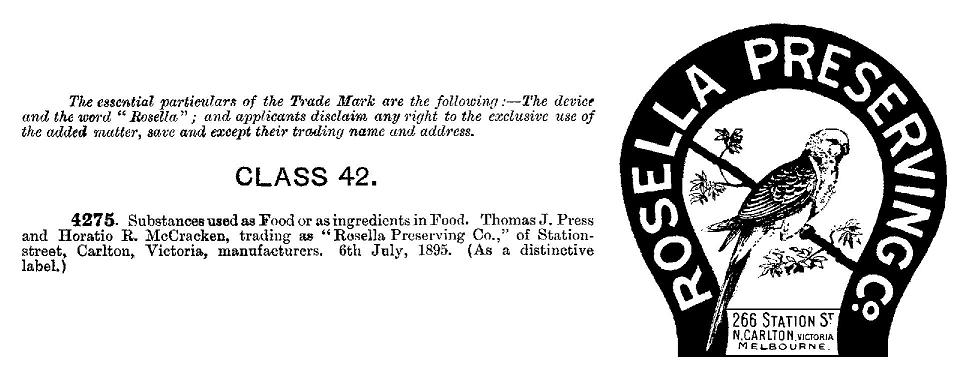

The Flight of the Rosella

The iconic Australian brand name Rosella is traditionally associated with the Melbourne suburb of Richmond and the former factory site in Balmain Street, where the company's jams, sauces and preserves were manufactured until the 1980s. It may come as a surprise that Rosella had its origins in North Carlton, a decade before the Richmond factory was established in 1905. Rosella's founders Horatio McCracken, a commission agent, and Thomas Press, a grocer, began making jam as a backyard business in the 1890s. In July 1895, they registered the Rosella Preserving Company trade mark, with the familiar horseshoe shape and rosella bird image. The address of 266 Station Street, North Carlton, was originally a brick blacking factory built by James Dunster in 1880 or 1881. The factory was on a double block, measuring 36 x 100 feet, and was owned by the Royal Insurance Company from 1893 to 1898. In November 1895, the Rosella Preserving Company Limited was registered, with an office address of 134 and 136 Flinders Street, Melbourne. According to rate book records, McCracken and Press occupied the North Carlton factory site in 1896. The following year, in November 1897, the Rosella Preserving Company moved to Errol Street, North Melbourne, in premises previously occupied by King, King & Co. The next major stage of development occurred in 1905, when Rosella moved into purpose-built premises in Richmond in 1905. 1,2,3,4,5,6

Image Source: Victoria Government Gazette, 12 July 1895, p. 2650

There are several theories of how the brand name Rosella came about. The official version, from Rosella's published history, is that a flock of rosellas flew over while McCracken and Press were making jam in their backyard in Carlton. This explanation has merit as the rosella bird image appears on the trade mark, but why would McCracken and Press, neither of whom lived in Carlton, be making jam in the backyard when they had access to the factory? Another explanation is that Rosella is a compound word of "Rose" and "Ella", the names of the daughters of McCracken and Press. This family connection is unproven and no evidence of daughters with these names has been found in Victorian birth records. In any case, the female name "Rosella" was already in use in Victorian times. The third explanation is that McCracken and Press first made jam from rosella berries. The rosella plant, known by the botanical name Hibiscus sabdariffa, is a relative of the ornamental hibiscus. The flowers are attractive, though not as spectacular as the ornamental variety, and jam can be made from the outer part known as the calyx. But were rosellas available, in commercial quantities, in Melbourne in the 1890s? 7,8

Regardless of the origin of the brand name Rosella, the factory in Station Street played a small, but significant, role in the birth of an Australian icon. Following the departure of Messrs McCracken and Press and their jam making equipment, the factory served a completely difference purpose as a rabbit processing facility. Towards the end of 1898 Stephen Bishop, who lived next door at 264 Station Street, bought the factory and subdivided the land into two house blocks. He built two cottages, numbered 266 and 268 Station Street, on the site in 1899. 9,10,11

The Rosella brand was sold to Lever & Kitchen (later Unilever) in 1963, but has since been returned to Australian ownership. An updated version of the rosella image appears on the company's logo.12

Notes and References:

1 The Rosella story 1895-1963 : major events in the life of Rosella taken from early company records and the recollections of employees, 1977.

2 Victoria Government Gazette, 12 July 1895, p. 2650

3 Victoria Government Gazette, 22 November 1895, p. 3962

4 Victoria Government Gazette, 29 November 1895, p. 3999

5 Building ownership and occupancy information has been sourced from Melbourne City Council rate books and land title records.

6 North Melbourne Courier and West Melbourne Advertiser, 19 November 1897, p. 3

7 https://pocketozmelbourne.com.au/lost-rosella.html

8 A description of the rosella plant and a recipe for making jam appears at: https://www.selfsufficientme.com/fruit-vegetables/how-to-grow-rosella-make-it-into-jam

9 Sands & McDougall, 1897

10 Certificate of title vol. 1087, fol. 292

11 Australian Architectural Index

12 http://rosella.com.au/our-story/#history

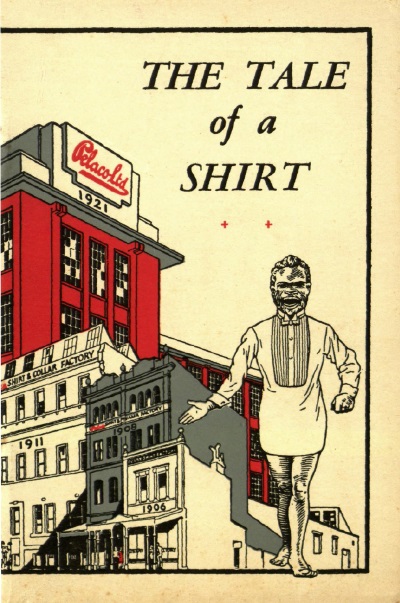

Shirtmaking in Carlton : How Pelaco got its Name

Digitised Image: State Library of Victoria The cover of a booklet from the 1930s features chronological images of the four Pelaco factories and "Pelaco Bill", the face of Pelaco's advertising.1 |

For over a century the brand name Pelaco has been synonymous with the shirt, a basic item of apparel that does much to define the wearer's social, economic and even criminal status. The terms "white collar" and "blue collar" are still in use today and shirts, fashionable or functional, are now worn by both men and women. In the early decades, Pelaco's advertisements featured images of Australian aborigines ("Mine tinkit they fit") and women ("It is indeed a lovely shirt sir") to sell men's shirts. While these advertising themes would be considered politically incorrect by today's standards, they have endured as part of Australia's popular culture. The Pelaco brand name was created from the first two letters of its founders' surnames, James Kerr Pearson and James Lindsay Law, and the abbreviation for the word "company", hence "Pe-la-co". In 1906, Messrs Pearson and Law formed a business partnership (Pearson Law) and began making shirts at the Derry Shirt Factory, 285 Drummond Street, Carlton. At the time, that area of Drummond Street, between University and Faraday streets, was a hive of manufactures. The shirtmakers' immediate neighbours were cap manufacturers, box makers, brush manufacturers and carpenters, with the Court House Hotel on the Faraday Street corner.2,3 The business was initally a small operation, with 12 machines and 18 employees, then it moved to larger premises in Gertrude Street, Fitzroy, in 1908 and Gipps Street, Richmond, in 1911, when the partnership became Pearson Law & Co Limited. The company went into voluntary liquidation in 1917 to enable formation of the public company Pelaco Limited. Shirts, collars and pyjamas were made at both factories until 1921, when Pelaco Limited moved to newly-built premises in Goodwood Street, Richmond. The distinctive Pelaco sign was installed in 1939 and has dominated Richmond's skyline for decades.4 After the departure of the shirtmaking business, the two-storey shopfront at 285 Drummond Street was home to the Carlton Club from 1910 to 1912. The building and adjoining properties (nos. 287 and 289) were owned by the department store, Ball & Welch, and used for warehousing and storage. The site has since been redeveloped and is now a commercial property. The Court House Hotel was delicensed in 1920.5,6

Notes and References: |

A Boy Named Carlton

Baby names can go in and out of fashion, but traditionally the surname is taken from the male parent, sometimes from the female parent, or a combination of both parents' names. How would an abandoned child of unknown parentage be named? In the 19th century, the practice was to present the child at the local court, which would then decide on its name and make an order for its care.

One such case heard by Carlton Court was an abandoned baby of about five weeks old. He was found on the doorstep of Mr McGuigan's house in Madeline (now Swanston) Street, Carlton, in August 1882. The baby was cared for overnight at the nearby Lying-in Hospital and brought to the court by a nurse the next day. He was remanded to the Royal Park schools (also known as 'industrial schools') while police tried to trace his parents. The investigations proved fruitless and the baby was once again called to appear in Carlton Court in September 1882. He was ordered to the Royal Park schools for a period of 15 years and registered under the name "William Joseph Carlton". According to his record in the Children's Registers, William was placed with various foster carers in Hotham (North Melbourne), Preston, Sandridge (Port Melbourne), Essendon and Brunswick. He absconded in July 1896 and was assigned to Mr Peterson at Clydebank in April 1897. His term of 15 years was due to expire on 20 September 1897, the anniversary of his original committal. Instead, it was extended to 1 July 1900, when he would have officially reached 18 years of age. The final record on his file is a statement, dated 28 April 1953, confirming his birth at Carlton on 1 July 1882.1,2,3

William was one of several abandoned babies who were named "Carlton" according to the location where they were found. In September 1876, a two month old baby was found by Mrs Jane Baker in the Carlton Gardens. He was subsequently named "William Carlton". Eight years earlier two infants were found in Carlton, on separate occasions in March and August of 1868. "Bertha Carlton", as she was later named, was found by architect Henry Bastow, and "Edward Carlton" was left on the doorstep of St Mark's parsonage in Nicholson Street. This was the home of the Rev. Robert Barlow and a note attached to the child's clothing expressed the mother's despair at being unable to care for her offspring.4,5,6

'The mother has done all that love and affection can suggest for her offspring, till poverty has driven her to resort to this means of placing it in the hands of the Ladies' Benevolent Society. She promises to contribute monthly, through the post, her mite towards its care and support.' 7

The mother's promise to contribute to her child's upkeep suggests that she was in a form of employment, possibly domestic service, that she could not maintain while caring for a young baby. Unfortunately, this was all too common at the time, when safe and affordable child care was difficult to find. Women, often poorly-paid single mothers, had to choose between earning enough money to support themselves, or keeping their babies in poverty.

Notes and References:

1 The Argus, 24 August 1882, p. 5

2 Children's Register No. 13653 (VPRS 4527)

3 A man named William Joseph Carlton died in Brunswick on 7 January 1954.

His death registration (No. 448/1954) states his parents as "unknown" and his age of 71 years at death is consistent with a birth date of 1 July 1882.

4 Children's Register No. 9593 (VPRS 4527)

5 Children's Register No. 2856 (VPRS 4527)

6 Children's Register No. 3157 and 8738 (VPRS 4527)

7 The Age, 1 September 1868, p. 2

Barry versus Barry

Barry Street and Barry Square

Sir Redmond Barry, the judge who famously sentenced Ned Kelly to death by hanging, had a long association with Carlton. He was the original crown land owner of two adjoining allotments in Rathdowne and Pelham Streets in 1853, and he lived in Carlton until the mid-1870s, when his substantial house was acquired and re-purposed as the new Hospital for Sick Children. Redmond Barry was appointed the first chancellor of Melbourne University in 1854, a position he held until his death in 1880. He was laid to rest in Melbourne General Cemetery, Carlton. The Victorian Heritage Database (B2376) attributes the naming of Barry Square in Carlton to Redmond Barry. However another, much younger, contender for the naming rights has emerged. The website Multifaceted Melbourne states that Barry Square was named after Daniel Joseph Barry, a Queensland soldier who was killed in action in World War 1 in October 1918, and that University Square was named as recently as 1998. Does this stand up to fact checking? 1,2,3,4

The crown grant, dated 13 June 1873, for the area bounded by Grattan, Leicester, Pelham and Barry Streets refers to "a public ground known as University Square". This name was in use as early as the 1860s, when it was common to name reserves according to their locality, hence "Barry Square" after Barry Street on the western boundary or "University Square" after the University of Melbourne on the northern boundary. Other examples in Carlton include Argyle Square and Macarthur Square, where the street names were used interchangeably with the names of the squares. This all took place decades before Daniel Joseph Barry was born in 1894 and more than a century before Barry Square was purportedly renamed University Square in 1998. So Daniel Joseph Barry's claim to naming rights does not fit within the established time frame. 5,6

Who was Daniel Joseph Barry? According to his service record (NAA: B2455, BARRY D J), he was born at California Creek, Herberton in Queensland in November 1894 and he was working as a clerk at the time of his enlistment. He enlisted at Townsville in October 1916 and was a private in the 7th Machine Gun Company and later the 2nd Machine Gun Battalion. Private Daniel Joseph Barry was killed in action in France on 3 October 1918, a young life cut short a month before his 24th birthday. In the months following his death, his family sought information about his final resting place. Months stretched into years and in May 1923 the Officer in Charge of base records wrote advising, with regret, that Grave Services had not succeeded in locating Private Barry's remains. The only consolation to the family was that Barry's name, regimental description and date of death would appear on a collective memorial to the fallen, to be "erected in certain defined battle areas of France or Belgium". There is no evidence in Private Barry's service record that his name was memorialised in Barry Square, Carlton, or that he had any known connection with the reserve in Carlton. 7

What would Judge Redmond Barry have made of this evidence? He certainly had a prior claim to the naming rights of Barry Street and Barry Square, in terms of both timeline and his connection with Melbourne University. Unlike the present day naming conventions, it was common to have streets and other landmarks named after prominent citizens during their lifetime. Redmond Barry's claim is backed up by evidence from authoritative sources, such as the Victorian Heritage Database, Melbourne City Council and Melbourne University. By contrast, Daniel Barry's claim consists of an unsupported statement on a web page that is now closed for comments. The verdict comes down in favour of Redmond Barry, but CCHG would be interested to hear of any information in support of Private Barry's claim.8,9

For more information on the squares of Carlton - Argyle, Curtain, Lincoln, Macarthur, Murchison and University - see our August 2018 newsletter.

Notes and References:

1 Australian Dictionary of Biography

2 The Argus, 28 September 1876, p. 7

3 Victorian Heritage Database (B2376)

4 Multifaceted Melbourne

5 Certificate of Title, Vol. 600, Fol. 912 (13 June 1873)

6 Argyle Square and Macarthur Square were permanently reserved on 13 June 1873, the same date as University Square.

7 NAA: B2455, BARRY D J (National Archives of Australia)

8 University Square Timeline

9 Melbourne University Key 13: Grounds and Buildings

North Carlton has three princely locations - Princes Hill, Princes Park and Princes Street. CCHG has recently been asked to research the naming of Princes Hill, the area north of Macpherson Street and west of Lygon Street. Our investigations have turned up several contenders for naming rights, all members of British royal family from the nineteenth century.

Prince Albert

The online Encylopedia of Melbourne attributes the naming of both Princes Park and Princes Hill to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the consort of Queen Victoria.

Only one reference is cited - Prinny Hill : The State Schools of Princes Hill 1889-1989 - and this book, in turn, gives a different interpretation.1

Prince Alfred

Prinny Hill attributes the naming of both Princes Park and Princes Hill to Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh and son of Queen Victoria.

Prince Alfred came to Victoria in November 1867 and is claimed to have visited the area that became Princes Hill, but was this location the same as Princes Hill the suburb?

There are several newspaper references to "Prince's Hill" and "Princess Hill" dating back the 1860s and one published in 1867, the same year as Prince Alfred's visit,

refers to "… the waste ground adjacent to Prince's-bridge, lying between the river bank and the Prince's-hill reserve ..."

This reference, and others from 1861, place "Prince's Hill" in the vicinity of the Yarra River and Prince's Bridge, for which it most likely named.

(Prince's Bridge, which opened in 1850, was named after Albert, the Prince of Wales.) 2,3,4,5,6,7

Prince Alfred's royal visit does not fit within the time fame for Princes Park. The area named as "Prince's Park" appeared on the Kearney map of 1855 and the land was permanently reserved in August 1864, three years before Prince Alfred's visit. So Prince Alfred is no longer a contender for the naming of Princes Park, but he could still be in the running for Princes Hill.

Prince Albert Victor and Prince George of Wales

Prince Albert Victor and Prince George of Wales visited Victoria in June and July of 1881.

They were Queen Victoria's grandchildren, and sons of Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales and heir to the throne.

Albert Victor died in 1892, and his younger brother George was later crowned King George V, following the death of their father King Edward VII.

The timing of their visit pre-dates the naming of Princes Hill by at least two years, and post-dates the renaming of Reilly Street to Princes Street.

Timewise, the two princes could be contenders for the naming of Princes Hill, but they miss out on Princes Street.8

Albert Edward, Prince of Wales

Wikipedia gives an unreferenced statement that Princes Hill was named after the Prince of Wales.

During Queen Victoria's reign, her eldest son Albert Edward was Prince of Wales and he became King Edward VII following her death in 1901.

Also according to Wikipedia, Prince's Park in Liverpool, England, was named after the Albert Edward (born in 1841) when it opened in 1842.

It is possible that Prince's Park (and hence the suburb of Princes Hill) was named after the Prince of Wales but,

in the absence of any documentary evidence, this is pure speculation.9

Princes Park and Princes Hill

The area named Princes Park appears on the Kearney map of 1855 and in 1856 The Argus describes the park as:

"… another fine piece of thickly-wooded land, separated from the former [Royal Park] by the Sydney road which, from the commencement of the parks to the Brunswick turnpike, runs between an avenue of splendid trees. This park extends on the other side to the Merri Creek and quarries. The availability of this park is impaired by its being open from the Sydney road, and traversed in all directions by cart-tracks."10

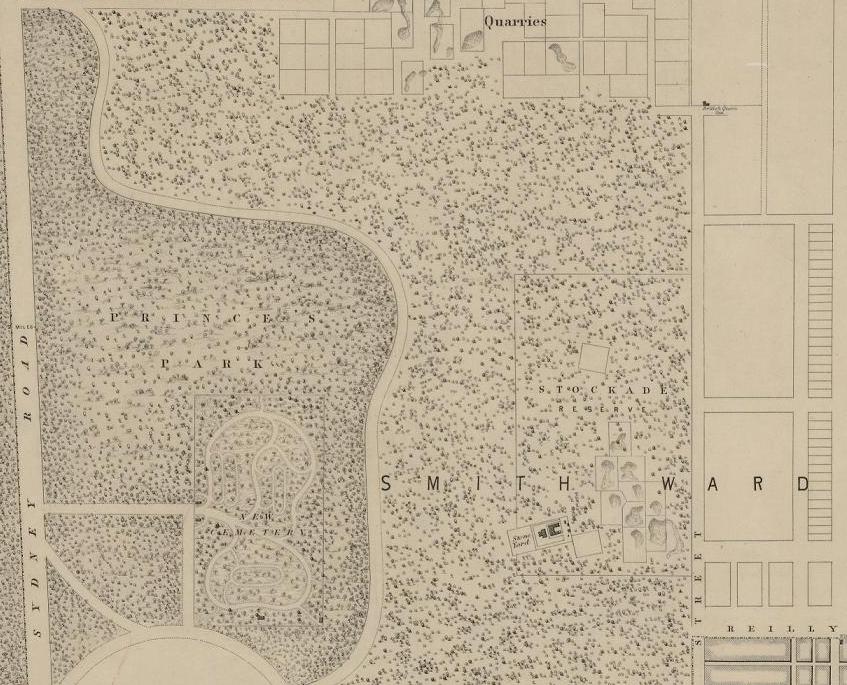

Digitised Image: State Library of Victoria

Portion of the Kearney Map of 1855

Showing location of Prince's Park, the Cemetery, the Stockade Reserve and Smith Ward.

Reilly Street (lower right hand corner) was later extended into Carlton and renamed Princes Street, circa 1880.

By the time the land was permanently reserved in August 1864, Prince's Park had been reduced to 84 acres, between Sydney Road to the west and the Cemetery and Princes Park Road on the east. The loss of parkland to the east and north of the cemetery was most likely done with a view to releasing crown land for future residential development. This happened in November 1869, when the new Victoria Ward was created from the northern portion of the existing Smith Ward. Crown land on the east side of Lygon Street north of Reilly Street was first released in 1870, and the area immediately north of the cemetery, which later became Princes Hill, in 1875.11,12,13

In July 1883, The Age and The Argus reported that a deputation of residents approached the Mayor of Melbourne requesting the area behind the cemetery to be named Prince's Hill. The proposal was positively received, as it did not involve the renaming of existing streets, and the seed of Prince's Hill as a suburb was planted.

PROPOSED PRINCE'S-HILL SUBURB.

An influential deputation of residents of North Carlton, accompanied by Crs. Richardson, Leonard and Alderman O'Grady, waited upon the Mayor of Melbourne, at the Town Hall, yesterday, to request that that part of North Carlton, at the back of the General Cemetery, should be definitely named. Mr. Gardiner, M.L.A., was also present. It was pointed out that the designation, "at the back of the cemetery," was not agreeable to the ratepayers, and they asked that the locality should be named Prince's-hill. Mr. Dodgshun, in reply, said that if the deputation would forward to him their wishes in writing it would be brought before the City Council at its next meeting, when, as the names of the streets would not be interfered with, he had no doubt the wishes of the deputation would be granted.14,15

The phrase "should be definitely named" is interesting and suggests that the name Prince's Hill may already have been in informal use prior to the deputation, and Council approval was a foregone conclusion. The proposal was considered at a Council meeting on 23 July 1883 and referred to the Public Works Committee. By October 1883, the name Prince's Hill began to appear in Council minutes and in real estate advertisements, as distinct from the suburb of North Carlton. Both suburbs remained within Victoria ward. The apostrophe was later dropped from the names of both Prince's Park and Prince's Hill, probably for the convenience of signwriters and typesetters. However, the misnomer "Princess Hill", which sometimes appeared in newspapers in the early days, still persists today.16,17

Which Prince?

The question of which prince gave his name to a suburb thousands of miles away from his home country is still open. Princes Hill has close historical and geographical links with Princes Park, as the area north of the cemetery was once part of the same park. The suburb may well have been named after Princes Park, in which case Prince Albert and his son Albert Edward could be rivals for the naming rights. Prince Alfred's visit of 1867 does not fit into the time frame for the naming of either Princes Park or Princes Hill. The younger Princes - Albert Victor and George - may have some claim to the naming of Princes Hill (but not Princes Park) in terms of the timing of their visit in 1881.

None of these claims is supported by firm documentary evidence and CCHG is seeking your help. Contact us if you can shed any light on the naming of Princes Hill.

Notes and References

1 Brian Carroll. Princes Hill, Encylopedia of Melbourne

2 Nicholas Vlahogiannis. Prinny Hill : The State Schools of Princes Hill 1889-1989, p. 5

3 The Age, 30 November 1867, p. 5

4 The Argus, 6 March 1867, p. 4

5 The Herald, 29 October 1861, p. 6

6 The Argus, 3 December 1861, p. 6

7 Port Phillip Gazette and Settler's Journal, 21 March 1846, p. 2

8 Melbourne and its suburbs, 1855 (Kearney map)

9 Victoria Government Gazette, no. 77, 2 August 1864, p. 1670

10 The Argus, 25 June 1881, p. 8

11 Wikipedia is a wonderful resource, but the information content is variable in accuracy and subject to revision.

The entries for Princes Hill and Prince's Park (Liverpool) were accessed 5 March 2019.

12 The Argus, 8 February 1856, p. 4

13 Victoria Government Gazette (see note 5 above)

14 Victoria Government Gazette, no. 61, 5 November 1869, p. 1767

15 Parish Plan of Jika Jika, M314 (14) and land title records.

16 The Age, 12 July 1883, p. 7

17 Minute Books of Council Meetings, 1883, p. 509 and 568 (VPRS 8910)

|

Notes and References:

|

|

Westray Villa

From the Orkney Islands of Scotland

Image: CCHG

Westray Villa

248 Canning Street, North Carlton

Westray Villa in Canning Street, North Carlton, was the home of the Cormack family from the 1880s through to 1960. To explore the origin of this house's name, we travel back to a remote island off the coast of Scotland and follow the journey of a young woman who made a life-changing – and almost life-threatening – choice in the mid-19th century. Phoebe Papley (Paplie) was born in 1833 (or 1834) at Westray in the Orkney islands of Scotland. Westray, while not the smallest of the Orkney islands, is only 18.2 square miles or 47 square kilometres in area and, in the 19th century, would have offered limited opportunities for earning a living and supporting a family. Phoebe was the daughter of James Papley and Barbara (Barbra) Skee (Skea, Skae or Skay) and the Scotland census of 1841 recorded four residents in the household at Dogtua (Dogtuan) as:

Name Age Birth Year Birth Place Barbra Paplie 45 years 1796 Orkney, Scotland Febey Paplie 8 years 1833 Orkney, Scotland Jane Paplie 5 years 1836 Orkney, Scotland Mary Paplie 40 years 1801 Orkney, Scotland

In the 1851 census Phoebe was no longer listed as living at Dogtua. In the same census year, a young woman named "Phoebe Pably", aged 18, was recorded as a servant living in the household of Stewart and Mary Logie at Ark House in Westray. A year later, in 1852, Phoebe left her island home to embark on an eventful journey to a new life in Australia. She was described in the passenger list as a domestic servant of the Presbyterian religion and, unlike many of her fellow passengers, she could read and write. Phoebe was not alone on the voyage, as her older brother James, sister-in-law Jessie (Janet) and their two children, also named James and Jessie, were on the same ship. Phoebe's name appears on a different page of the shipping list, suggesting that she was housed separately in the single women's quarters, in line with ship boarding practices at the time.1,2,3,4,5

The Papleys were among an estimated 795 Scottish, English and Irish passengers and 48 crew aboard the ill-fated emigrant ship Ticonderoga. The American-built ship was fitted out to maximise the number of passengers carried and, while there was sufficient food on board for 120 days, there was no provision for the ship to take on fresh food and water during the non-stop voyage. The Ticonderoga sailed from Liverpool on 4 August 1852 and arrived at Port Phillip Heads 3 months later on 3 November, flying the yellow "plague" flag. The double-deck ship was overcrowded and unsanitary conditions on board led to the rapid spread of disease, reported as scarlet fever and the even more deadly typhus fever. 100 passengers died during the voyage and were buried at sea. The ship was denied entry to Port Phillip Bay and the passengers – the living, the dead and the dying – were offloaded at a remote beach near Point Nepean. Having endured three months at sea in appalling conditions, the survivors now faced an indeterminate period of quarantine until the disease had run its course. For Anglo-Celtic people accustomed to a colder climate, the first glimpse of their new home with its strange coastal vegetation would have been bleak. A makeshift camp of tents was set up, but this offered little protection from the hot Australian sun and the inevitable flies. Once the news of the Ticonderoga's plight had reached Melbourne, supplies of fresh food and medicine were despatched to Point Nepean. The hulk Lysander was fitted out as a hospital ship to accept the more serious cases, many of whom died. The dead were buried, often by their grieving relatives, in the sandy soil and their graves were marked by rough stone or wooden markers. The official death toll was 168 passengers and 2 crew, but it is thought to be higher as some deaths went unreported. The Papleys survived and arrived at Hobson's Bay, just before Christmas, on 22 December 1852, nearly five months after their departure from Liverpool.6,7,8

James Papley, an agricultural laborer, was engaged by William Gillespie, a tailor, of Belfast (an early name for Port Fairy) and he headed off to work in the western district in January 1853. There was a demand for workers as many had abandoned their posts to seek their fortunes on the goldfields. James and his wife Jessie had three more children – two sons named Robert in 1854 and 1857, the first of whom died in 1855, and William in 1859. When the new Belfast Hospital and Benevolent Asylum was opened in 1856, James and Jessie Papley were appointed as Master and Matron. There were concerns expressed about their suitability for the positions, particularly in relation to Mrs Papley, and allegations were made of mismanagement of inmates and financial resources. They were dismissed in 1858, then re-instated to the positions, which they held until 1871, when Mr and Mrs Mainwaring were appointed. The Papley's reputation was not enhanced by an allegation of indecent assault in 1869, involving their teenage son James and Phoebe Mott, a servant at the hospital. The incident and subsequent inquiry were considered of sufficient importance to be published in the Melbourne newspapers.9,10,11,12

If even a portion of what the Banner of Belfast states concerning the local hospital be true, the hospital committee would appear to be very lenient in discharging their duty, to say the least : – "We learn that the committee appointed to investigate the charge made by the girl Mott have virtually shelved the case. We are also informed that notwithstanding that the committee were specially instructed to inquire into the general management of the hospital, no such inquiry was made ; on the contrary, that those anxious to do so were obstructed. From the time of this occurrence there seemed a very anxious desire to hush it up, and the girl was prevented laying a [sic] criminal information against Papley. In her subsequent statement she does not accuse him of any criminal intent, but this was after certain influences were exerted to silence her. If she had been of that opinion at first, why go to the police court to lay informations [sic] against Papley? Papley's statement that the affair was a 'lark' is not worthy of belief. Neither is it consistent with his statement that he was about to destroy himself because his father had compelled him to go to Mr Burnett's revival meeting, where he met the girl Mott. If the committee believed that statement they would have had him arrested as a dangerous lunatic. There can be no doubt that the girl was tampered with, from the discrepancy between her written statement and that made by her at the police office. That the committee stood between the culprit and the law – that they burked the inquiry into the general management of the hospital – is proof sufficient that the investigation was a mere sham. To delay inquiry for three weeks, until the matter was quietly arranged, looked also like a pre-determination to hush up the affair."

Phoebe Papley's first few years in Australia are unknown - she may have gone to Belfast with James and his family, or she may have stayed in Melbourne and obtained a position as a domestic servant. In 1856, Phoebe had another life-changing event when she married a fellow Scot named William Cormack. William, born in Wick, Caithness, in 1825, was a tailor by trade and the 1841 Scotland Census confirms that he was an apprentice at the age of 15. According to Victorian birth and death records, William and Phoebe had eight (possibly nine) children. The first recorded birth was Barbara Jane in 1857, followed by Rachel in 1858. There was an unrecorded birth of a daughter named Phoebe and, working back from her age at death, her year of birth would have been circa 1857, the same as Barbara. As there is no further record of Barbara, it is possible that she was re-named Phoebe. The next daughter, Jane, did not live to her first birthday. She was born in 1861 and died in December of the same year. Then came two sons, William Donald in 1862 and James Robert in 1865, and another daughter Jessie Elizabeth in 1868. Two more sons, George Alexander and John Papley, were born in 1870 and 1872, but George died in 1874 at the age of 4. The family lived in a three room brick house in Faraday Street, Carlton, and William Cormack also owned the adjoining house, which was rented out. (At the time, the houses were numbered 85 and 87, but were changed to 110 and 112 Faraday Street in the late 1880s.) Young Phoebe must have wandered from home in May 1860, when Mr Cormack placed an advertisement in the public notices of The Argus for a lost child. It may seem strange to advertise a lost child in the same manner as you would a lost animal, but child supervision standards were different in the 19th century compared to those of today.13,14,15,16,17

By the 1870s, the Cormack family was rapidly out-growing the three room house in Faraday Street and in the same decade land allotments became available in the new suburb of North Carlton. The prison stockade had closed in 1866 and the lunatic asylum, which replaced it, closed in 1873. The old asylum site was taken over by the Education Department and a new school (originally called the Stockade School and now Carlton North Primary School) opened in July 1873, encouraging families with children to move into the area. One of the early crown land owners was George Williams of Carlton, who bought four allotments in section 86, the area bounded by Canning, Yorke (later Lee) and Station Streets in 1870. He paid £280 for allotment 4, containing 1 rood and 12⅖ perches. The crown allotment originally stretched all the way back to Station Street but, after subdivision, the block of land purchased by William Cormack in 1880 measured 17 feet 6 inches wide by 102 feet deep. In the same month the land purchase was registered, October 1880, a notice of intent was lodged by John Wright – a builder of Lygon Street, Carlton – for a five room cottage in Canning Street. The owner's name is recorded as "Cormick" and, given the street location and coincidental dates, this construction was quite possibly Westray Villa. The new house first appears in the Melbourne City Council rate books in 1881 and is described as a "four-roomed brick house with verandah and bathroom". From 1889, there were indications that the house had been extended because room count had increased to eight.18,19,20,21,22,23

In 1891, Phoebe participated in a significant event that had far-reaching implications for generations of women who followed her. The so-called "Monster" petition in support of the vote for women records three signatories at the address of 248 Canning Street, North Carlton – J. Cormack, P. Cormack and Mrs Cormack. The first signature was most likely Phoebe's daughter Jessie and the second Phoebe junior. The petition was tabled in the Parliament of Victoria in September in 1891, but it was not until 1902 that women were allowed to vote in Commonwealth elections and 1908 in Victorian elections. The Commonwealth electoral roll for 1903 lists five registered voters living at Westray Villa. Jessie was unmarried and still living at home, together with her mother Phoebe and her brothers James, John Papley and William Donald Cormack.24,25,26

Name Address Occupation Cormack, James 248 Canning Street, North Carlton Plasterer Cormack, Jessie 248 Canning Street, North Carlton Home duties Cormack, John Papley 248 Canning Street, North Carlton Clerk Cormack, Phoebe 248 Canning Street, North Carlton Home duties Cormack, William Donald 248 Canning Street, North Carlton Weigher

Tragedy struck Westray Villa in 1897. Phoebe was no stranger to death – she had witnessed the events on board the Ticonderoga and she had lost two of her own young children – but the loss of another daughter and her husband, within months of each other, was almost too much for a wife and mother to bear. Her daughter Phoebe died at home on 15 April, aged 39 years, and was buried on Good Friday of 1897. Seven months later, on 1 November, her husband William died. According to his probate documents he died intestate (without leaving a will) and it was some years before his estate was finally wound up. His main asset, according to the documents, was the house in Canning Street, valued at £475, and furniture valued at £15. No money or personal items were recorded. Letters of administration (in lieu of probate) were granted to Phoebe, with a note signed by her in March 1901 stating "The house and land in Canning Street is still retained by me. That being the only asset in the estate." However, Phoebe's name does not appear as proprietor on the certificate of title and her husband's estate was not duly administered until 1920. Phoebe had a place to live, but she may have had little in the way of financial assets. Her financial situation could possibly explain a curious advertisement that appeared in The Age in October 1900.27,28,29

At the time, it was not uncommon for maternity services to be offered in private houses. Mrs Power may have been a registered nurse, or an experienced midwife, and the attendance of a doctor was likely to inspire confidence in her services. Phoebe may have, through financial necessity, rented out one or more of the eight rooms in the house to Mrs Power for maternity purposes.

Phoebe Cormack signed her last will and testament on 6 November 1900, leaving her estate in equal shares to her children William Donald, James Robert, Jessie Elizabeth and John Papley Cormack. Phoebe's address stated in the will was 457 Canning Street, North Carlton, though her name continued to be listed as the occupier of 248 Canning Street in Sands & McDougall directories.30

Phoebe's second daughter Rachel was not named in her will. Rachel had contracted scarlet fever as a child and may have suffered brain damage from complications of the disease. Rachel was diagnosed with "idiocy" and committed to Kew Lunatic Asylum at the age of 19. She was transferred to Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum in June 1880 and she spent the rest of her life there as a state patient. Rachel died in the asylum hospital on 24 February 1914. Her mother Phoebe died a few weeks later at Westray Villa, aged 80 years. Phoebe's death notice appeared in The Age of 21 March 1914.31,32,33

Interred privately Saturday, 14th. A patient sufferer at rest. Deeply regretted.

Eight months later, Phoebe's brother James Papley died in Portland, aged 88 years. That Phoebe and James cheated death on the Ticonderoga and both lived into their eighties is a testament to the strong constitution of their Westray ancestors.

"In a recent issue we recorded the death of Mr James Papley, senior, of Narrawong, which occurred at his son's residence, Percy-street, Portland, on September 25, and whose remains were interred in the Narrawong cemetery on the Sunday following, the funeral being largely attended. The deceased, who was 88 years old, was a very old colonist, he having arrived in Australia in the year 1852 in the ship Tyconderoga [sic] from Orkney Island, Scotland. He and his wife took the position of master and matron of the first Port Fairy hospital, which they held for a number of years. He afterwards took to farming in the Narrawong district, where he lived for 43 years. Deceased leaves three sons, a number of grandchildren, and great grandchildren." 34

Phoebe's estate was valued at £208, 6 shillings and 8 pence, with the amount £158, 6 shillings and 8 pence listed as "interest in a deceased person's estate." This was equivalent to a one third share of her husband's real estate, valued at £475 in 1898. Probate was granted to her elder sons William Donald Cormack and James Robert Cormack. At the time of Phoebe's death in 1914, her husband William's estate had not been duly administered – she may have simply omitted to complete the paperwork – and this generated a second application for letters of administration in 1920. William Donald Cormack, the eldest son of William and Phoebe Cormack, applied for "administration of the unadministered estate" of his father in August 1920. In the application he states that the house, then valued at £680, was occupied by his sister Jessie Elizabeth Cormack, his brothers James Robert Cormack, John Papley Cormack (crossed out) and himself. His explanation for the time delay in application was that he was not aware of the requirement until he consulted his solicitors.35,36

James Papley junior's son Leonard was killed in action at Gallipoli in 1915 and, two years later, James died in Portland in 1917. His obituary, published in Port Fairy Gazette, stated that he was born in the Orkney Islands and came to Australia as an infant:

"Mr James Papley, an old and respected resident of Portland, died on Sunday morning last, after a brief illness. He was born at the Orkney Is. in 1852, and came to Australia with his parents in his infancy. His father was superintendent of the Port Fairy hospital for some time, and afterwards took up farming at Narrawong. Deceased was a carpenter and joiner by trade, and carried on business at Portland up to the time of his death. He held a seat for a short term on the hospital board, and was a member of the cemetery trust. He leaves a widow, two sons (Fred and William) and three daughters (Maisie, Eileen and Kathleen) to mourn his loss. One of his sons (Leonard) was killed at Gallipoli a few days after the memorable landing, and his daughter Alma died a few months ago. The funeral left All Saints' R.C. church on Tuesday for the South Cemetery." 37,38

Phoebe's younger sister Jane Papley, a needlewoman and dressmaker, migrated to Australia in later life and she died in Camberwell in 1923 at the age of 85 years, once again a testament to the Papley family's longevity. She was buried in the Cormack family grave in Melbourne General Cemetery. Death visited the Cormack family again in 1928, with the uncanny repetition of two funerals within a few months of each other. Jessie Elizabeth Cormack died at home, aged 61 years, followed by her brother James Robert Cormack, aged 64 years, at a private hospital in Fitzroy. Ownership of Westray Villa was transferred to the two surviving Cormack brothers, William Donald and John Papley. William Donald Cormack died on 24 November 1940, aged 78 years, followed by his brother John Papley Cormack on 23 August 1956, aged 84 years. The death of John Papley Cormack, in the centenary year of his parents' marriage, was the final link with Westray Villa and the young woman who had left her homeland in 1852. Probate was granted to John's children – John Henry Cormack of 197 Station Street, North Carlton, and Florence Jane Phoebe Cormack of 248 Canning Street, North Carlton. The house changed ownership in 1960, ending 80 years of continuous ownership and occupancy by the Cormack family. Over the years, the house has undergone some modifications, but the original brick structure and the name "Westray Villa" on the parapet remain essentially the same.39,40,41,42,43

Phoebe's final resting place is in Melbourne General Cemetery, not far from Westray Villa in North Carlton. She and William are buried in an unmarked grave in the Presbyterian compartment, together with their children Jane, George and Phoebe. Backing onto this grave is another of more recent burial, marked out and identified only by a number, where Rachel, Jane Papley, Jessie, James and William Donald are buried. John Papley Cormack is buried in a separate unmarked grave with his wife Florence Matilda Holyoake, who he married in 1908. Nearby there is an elaborate monument to the Orkney family, a reminder that others in this sea of graves might share their ancestral roots with the Orkney Islands of Scotland.44,45

Postscript

In the aftermath of the Ticonderoga tragedy, questions were asked and blame was laid variously on the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission (for chartering the ship), the ship owners (for seeking profit at the expense of passenger health and safety), and, by no less a personage than Lieutenant Governor Charles La Trobe, the passengers themselves for not keeping their quarters clean. A positive outcome from the tragedy was that double-deck ships were no longer to be used for emigrant transport and passenger numbers were restricted, particularly for infants and young children, who had higher mortality rates. The Ticonderoga had its final voyage, in either 1872 or 1879, when it was wrecked off the coast of India.46,47

A permanent quarantine (or sanitary) station was established at Point Nepean – the area having been fortuitously selected for the purpose some months prior to the arrival of the Ticonderoga – and it provided an essential public health service for nearly a century and a half, by containing infectious diseases before they reached the populated areas of Victoria. In the chaotic early days of setting up the station, able-bodied stonemasons and carpenters amongst the passengers of the Ticonderoga were engaged to build structures to house passengers and staff. Some of these tradesmen elected to stay and settle in the area, as work was guaranteed and the pay was good. The area where the Ticonderoga passengers first came ashore in 1852 became known as Ticonderoga Bay. This bay is now a dolphin sanctuary and the sociable marine mammals frolic in the waters once sailed by the plague ship Ticonderoga.48,49

Finally, we return to the ancient island of Westray. In 2009, an archaeological dig uncovered a 4 cm carved Neolithic figurine, the first one of its kind to be found in Scotland and the earliest depiction of a human face found in the United Kingdom. The stone figurine was dubbed the "Westray Wife" and, in the local parlance, the term "wife" can mean any woman, regardless of her marital status. Phoebe Papley was a young Westray woman when she left her homeland in 1852 and she became a Westray wife when she married William Cormack in 1856. The connection between the "Westray Wife" and the house in Canning Street is tenuous, but intriguing.50

A Note on Sources:

Information on the history of the house known as Westray Villa is taken from Research into 248 Canning Street, North Carlton.

(National Trust of Australia. Victoria) This document includes some biographical information on the Papley and Cormack families and, where sources exist,

these records have been cross-checked with immigration and shipping records; birth, death and marriage records; census records ; probate documents ; land titles and electoral rolls.

Michael Veitch's 2018 publication Hell ship : The true story of the plague ship Ticonderoga, one of the most calamitous voyages in Australian history gives a detailed account of life and death on board the Ticonderoga, and the events that led to the tragedy.

The Port Fairy Historical Society provided information on the family of James Papley and their assistance is gratefully acknowledged.

Special thanks to Jodie Linney (née Cormack) for additional information on Rachel Cormack.

References:

1 Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

2 Scotland Census 1841

3 Scotland Census 1851

4 Assisted and Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1839–1923

5 According to the Scottish Girls Names website, the names "Jessie" and "Janet" are synonymous.

6 Michael Veitch. Hell ship : The true story of the plague ship Ticonderoga, one of the most calamitous voyages in Australian history.

Allen & Unwin, 2018

7 Scarlet fever and typhus are bacterial diseases, which can now be treated with antibiotics.

The mode of typhus transmission via human body lice was not understood until the 20th century.

8 Some sources state that James Papley's infant son James died either during the voyage or in quarantine, but his name does not appear on the list of deaths.

The birth of a child named James was registered to James and Jessie Papley at Belfast (Port Fairy) in 1853.

James Papley junior's obituary, published in the Port Fairy Gazette of 28 June 1917, states that he was born in the Orkney Islands in 1852.

9 Marten A. Syme. Seeds of a settlement : a perspective of Port Fairy in the second half of the nineteenth century through

the surviving buildings and their inhabitants, 1991, p. 134-135

10 Hamilton Spectator, 12 April 1871, p. 4

11 The Age, 17 July 1869, p. 2

12 Victorian birth records confirm that Phoebe Mott was a local girl, born in Belfast in 1851.

She would have been about 18 years old at the time of the alleged assault.

13 Scotland Births & Baptisms 1564-1950

14 Pioneer Index. Victoria 1836-1888

15 The births of some of the Cormack children are recorded with the maternal name variations of "Phebe", "Popley" and "Possley".

16 Building ownership and occupancy information on the Faraday Street houses is sourced from Melbourne City Council rate books (Smith and Victoria wards).

17 The Argus 16 May, 1860, p. 6

18 Certificate of title, vol. 367, fol. 258

19 Certificate of title, vol. 1204, fol. 768

20 Notice of Intent, reg. no. 8539, 8 October 1880 (Australian Architectural Index)

21 Melbourne City Council, Victoria Ward, 1881, no. 2538. Note: Bathrooms were sometimes included in the overall room count.

22 Melbourne City Council, Victoria Ward, 1881, no. 2108

23 https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/static/WomensPetition/pdfs/434.pdf

24 Australian Electoral Commission

25 Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Northern Melbourne, 1903

26 The Age, 7 April 1897, p. 3

27 The Age, 3 November 1897, p. 8

28 Letters of Administration of William Cormack's estate, 67-101 (1898) (VPRS 28)

29 The Age, 6 October 1900, p. 6

30 Last will and testament of Phoebe Cormack (140-166) (VPRS 7591)

31 Case books of female patients, 1878, p. 21-22 (VPRS 7397)

32 Inquest deposition file 158-1914 (VPRS 24)

33 The Age of 21 March 1914, p. 5

34 Port Fairy Gazette, 2 November 1914, p. 2

35 Probate File of Phoebe Cormack, 140-166 (1915) (VPRS 28)

36 Letters of Administration of William Cormack's estate, 172-678 (1920) (VPRS 28)

37 NAA: B2455, PAPLEY LEONARD (National Archives of Australia)

38 James Papley's death notice in Port Fairy Gazette, 28 June 1917, p. 2

39 Jane Papley's occupation is listed as "Ayreshire Needlework" in the Scotland 1861 Census and "Dressmaker" in the Scotland 1881 Census.

40 Dates of death are confirmed by probate documents (where applicable), newspapers notices or Melbourne General Cemetery records.

41 The Age, 16 October 1928, p. 1

42 Certificate of title, vol. 1204, fol. 768

43 Probate File of John Papley Cormack, 508/623 (1956) (VPRS 28)

44 Melbourne General Cemetery records

45 The marriage was reported in The Age, 30 January 1909, p. 5

46 Letter from Governor La Trobe to Sir John Pakington, 26 January 1853, quoted by Michael Veitch in Hell Ship, p. 242.

47 Wikipedia (accessed 14 March 2019) cites the year 1872, while Michael Veitch cites October 1879 in Hell Ship, p. 239.

48 The place name Ticonderoga Bay appeared in newspaper reports and the Victoria Government Gazette from 1853.

49 Wildlife (Marine Mammals) Regulations 2009 (Statutory Rule No. 143/2009)

50 The story behind the Westray Wife