Carlton is well known for its network of small and narrow streets and laneways, a legacy of largely unregulated subdivision and speculative building activity in the 19th century. In the 1930s, many of these streets were condemned as slum pockets and under threat of demolition. Over the decades, some streets have been swallowed up by residential and commercial developments, others have been re-born as new streets, while a few have survived remarkably intact. This page - a work in progress - is dedicated to stories of the small streets of Carlton, and the people who lived and worked there.

Digitised image: State Library of Victoria

1MMBW Detail Plan 1188, 1897 (Digitised copy, State Library of Victoria) 2 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Victoria and Smith Wards, 1872 to 1939 3 Probate File 282/418, 1936 (VPRS 28) 4 The Argus, 28 August 1936, p. 12 5 The Argus, 29 August 1936, p. 16 6 The Argus, 18 August 1915, p. 5. 7 First (Progress) Report of the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board (1936-37), p. 7 8 The Argus, 2 July 1940, p. 2 9 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Smith Ward, 1941 to 1959-60 10 The Argus, 28 June 1913, p. 2 11 House occupancy information sourced from Sands & McDougall 1873 to 1941 12 Inquest Deposition File 1903/1188, 1903 (VPRS 24) 13 The Argus, 18 April 1898, p. 6 14 The Argus, 7 February 1924, p. 13 15 Divorce Case File 1930/279, 1930 (VPRS 283) 16 Marriage Index Victoria, reg. no. 16726, 1940 17 Central Queensland Herald, 19 September 1940, p. 35 18 Inquest Deposition File 1940/1383, 1940 (VPRS 24) 19 The shooting incident and subsequent trial were reported in The Argus and other newspapers from April to July 1944. 20 Jean Dowling's age was stated as 15 years old in some newspaper reports, but Death Index Victoria reg. no. 5419, 1944 confirms that she was 14. 21 Divorce Case File 1930/279, op cit, and the Victorian Electoral Roll confirm that Violet Grace Toner lived at 458 Canning Street North Carlton. 22 The Argus, 19th July 1944, p. 6 |

Carlton |

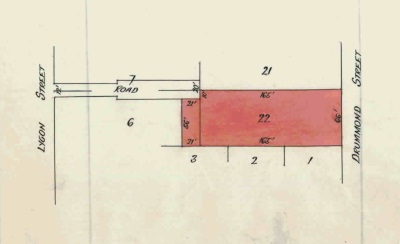

Source: Extract from Certificate of Title, Vol. 4438, Fol. 468 Plan of Christopher Glynn's Allotment The road from Lygon Street is York Place

Digitised image: State Library of Victoria Carlton Place Carlton, off Drummond Street, in the 1930s. 1 MMBW Detail Plan 1187, 1897 (Digitised copy, State Library of Victoria) 2 The two other streets named Carlton Place were off Lygon Street, between Earl and Queensberry Streets, and off Madeline (Swanston) Street, near Queensberry Street. 3 Biographical information has been sourced from birth, death and marriage records. 4 New South Wales Shipping Records, Assisted Migrants 5 In quarantine : a history of Sydney's quarantine Station 1828-1984. Kangaroo Press, 1995, p. 55-57 6 Melbourne General Cemetery records 7 Certificate of title application file no. 10602 (VPRS 460) 8 The Age, 9 November 1858, p. 5 9 All Saints Church of England 1858-1958, souvenir booklet, p. 8-9 10 The All Saints Church was built in stages over several years and the initial contract awarded to Christopher Glynn was for laying the foundations to plinth level only. Two other builders were contracted to build the walls and roof. 11 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Smith Ward, 1859-1874 12 The Argus, 20 July 1860, p. 1 13 The Argus, 7 June 1862, p. 4 14 Declaration, dated 29 December 1869, by Christopher Glynn in certificate of title application file no. 2295 15 Certificate of title application file no. 42616 (VPRS 460) 16 Certificate of title application file no. 2295 (VPRS 460) 17 Certificate of title, vol. 275, Fol. 998 18 The Argus, 15 July 1874, p. 8 19 Victoria Government Gazette, 5 July 1872, p. 1268 20 The insolvency was declared a few weeks after the marriage of Christopher Glynn's daughter Mary to Lambton Le Breton Mount at St Peter's Eastern Hill on 17 June 1874. 21 The Advocate, 4 July 1874, p. 9 22 Land ownership information has been sourced from certificates of title previously cited. 23 Weekly Times, 5 August 1882, p. 13 24 Melbourne General Cemetery records 25 The Argus, 13 November 1897, p. 10 26 Probate File 149/822, 1917 (VPRS 28) 27 First (Progress) Report of the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board (1936-37) 28 Certificate of title, vol. 9786, fol. 027 (consolidation plan) and preceding titles. |

Carlton |

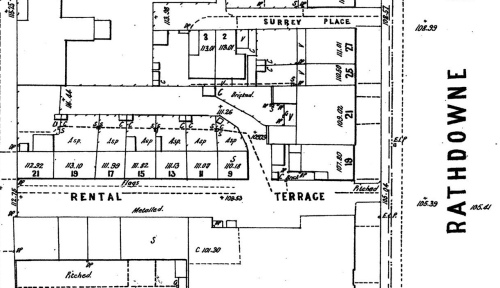

Extract from MMBW plan no. 1180 & 1181 (Digitised copy, State Library of Victoria) Rental Terrace Carlton (as surveyed in 1896)  Image courtesy of Bill Owens Owens & Dixon Bakery in Victoria Street Carlton (circa 1919-20) The western wall of Queen's Coffee Palace is on the right and the rooftops of Rathdowne Terrace are just visible in the background.

1 Parish plan of Jika Jika M314(14), County of Bourke 2 The Argus, 23 August 1853, p. 1 3 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Gipps Ward 1850-1855 4 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Smith Ward 1858 5 Australian Dictionary of Biography online 6 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Smith Ward 1860-1861 7 Probate file of Moses Rintel, no. 20/630, 1880 (VPRS 28) 8 Probate file of Elvina Rintel, no. 91/092, 1904 (VPRS 28) 9 MMBW plan no. 1180 & 1181, 1896 10 City of Melbourne Building Application index (VPRS 11201) |

Carlton |

Photo: CCHG Reeves Street Carlton, looking west towards Drummond Street

1 The Argus, 7 September 1867, p. 2 2 The Argus, 9 May 1868, p. 5 3 The Argus, 10 August 1868, p. 2 4 The Argus, 27 January to 13 February 1879 5 The Age, 1 October 1903, p. 6 6 The Argus, 1 October 1903, p.5 7 The Argus, 23 June 1916, p. 4 8 The Argus, 5 June 1926, p. 17 9 The Argus, 19 August 1931, p. 10 10 City of Melbourne, Town Clerks Correspondence File nos. 5460 and 5463-5468, 1939 (VPRS 3183) 11 The Age, 24 October 1939, p. 10 12 Freudenberg, Graham. Calwell, Arthur Augustus (1896-1973) (Australian Dictionary of Biography) 13 The Age, 3 August 1957, p. 7 14 Victoria Government Gazette, no. 256, 13 November 1957, p. 3610 15 City of Melbourne Rate Books, Smith Ward, 1957-1963 16 The Herald, 6 April 1961, p. 1 17 Victoria Government Gazette, no. 18, 13 March 1963, p. 581 |

Carlton |

Image: CCHG

Image: CCHG

Notes and References 1 Property ownership information sourced from land title records 2 Melbourne City Council Rate Books, Victoria Ward (VPRS 5708) 3 Melbourne City Council. Notices of Intent (Burchett Index) 4 MMBW Detail Plan 1158 5 Building Application File, BA 10595 (VPRS 11201) 6 The Argus, 21 July 1930, p. 7 7 Victorian Heritage Database 8 First (Progress) Report of the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board (1936-37) 9 Properties condemned under section 56 of the Housing Act 1958 (VPRS 1824) 10 Melbourne Times, 17 November 1976, p. 1 |

North Carlton |